Benefit nights are an integral part of the Georgian repertory. There are different kinds of benefit nights but they all share one essential characteristic: the theatre’s profit of the evening was given or shared with the beneficiary, usually subject to the house charge being met. The house charge was an estimate of the operational cost of opening the theatre’s doors for the evening. For most beneficiaries, their benefit night was an integral component of their remuneration package and could play a part in salary and contract negotiations. We describe the main types and our treatment of them below:

Author benefit

Author nights were the primary means of authorial remuneration in our period. They were largely allocated to writers of new mainpiece plays and entitled them to the profit of the house on the third, sixth, and ninth nights of their drama, should the run of the play last that long. In rare cases, for particularly successful plays, there might be additional ex gratia payments but, by and large, the 3-6-9 model held steady until 1794 when managers began to pay a fixed sum per performance (£33 6s 8d per night up to nine performances i.e. capping remuneration at £300, with another £100 on offer if the play managed twenty nights). Remuneration for afterpieces operated on a different, more opaque, model. Our data in this regard is much less well established, as already noted by Milhous and Hume (27-31), it might be generally observed that remuneration varied considerly more for afterpieces than mainpieces and sometimes flat fees were paid, although on rare occasions benefit nights would be granted should a piece be particularly successful. Depending on the dominant performance medium (see Works & Performances document) of an afterpiece, it is also common to see choreographers and composers receiving benefit nights for their labours in creating these productions; these are usually one-off and depend on the longevity of the afterpiece in the repertory.

A slight exception exists for plays authored by the theatres’ managers, where we see alternative arrangements and often deferred payments, rather than the 3-6-9 model. Managers, such as David Garrick and Richard Brinsley Sheridan, typically receive one-off sums for their plays, and are typically well remunerated – being exempt from the risk of a benefit and need to clear house charges. For example, the expenses detail a payment of £741 6d to Sheridan on 14 June 1777 for one night of A Trip to Scarborough and four nights of The School for Scandal.

Employee benefit

The vast majority of benefit nights held at the patent houses were those given to employees, both performing and non-performing. These nights could be contentious with dates and house charges varying according to status within the company and often attention had to be paid to whether there was a clash with a benefit at the other theatre. Certain dates in the calendar were often undesirable for a benefit night, such as St Patrick’s Day (17 March) or the Epsom Derby (held on a Thursday in late May/early June in our period from 1780). Employee benefits were usually held February to May with the more established stars taking their benefits on earlier dates (sometimes they also had clear benefits i.e. paid no charge to the house). Less well-regarded employees would share benefits, both risk and reward, and newcomers to the stage would often be permitted to sell a handful of tickets at another’s benefit night. Many people who would go on to have solo benefit nights – the ultimate mark of status – started out in this way, including Sarah Siddons on 29 April 1776. Beneficiaries sold tickets to their social network, either directly themselves at their home address, via a network of vendors (typically tradespeople or coffeehouses), and/or through theatre staff at the stage door; we have retained some of this geographic information in the notes on the Event (as always, we direct users to the London Stage for fuller information). Where box, pit, and gallery breakdown of ticket sales are available, they are an insightful marker of both social status and career progression. If door receipts failed to meet the charge, a debt to the theatre was incurred and a benefit deficiency had to be repaid from the beneficiary’s own pocket, although this was often (but not always) covered by ticket sales.

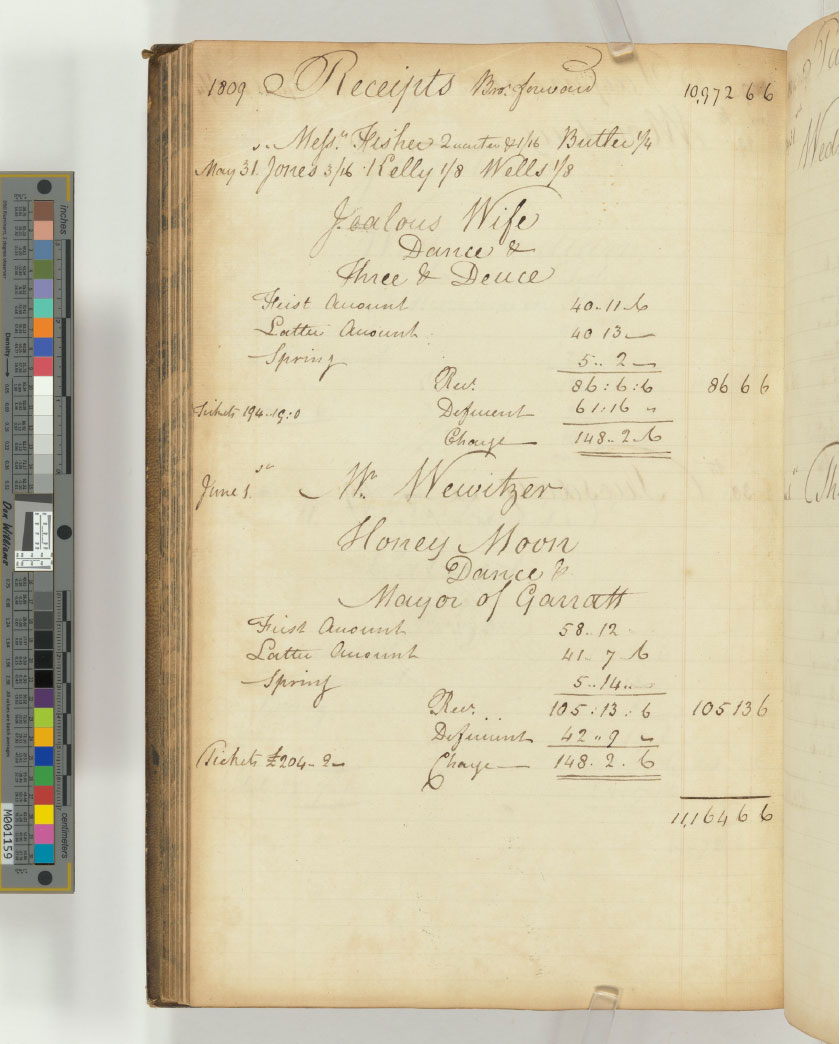

In this example of a benefit night, we see how complicated matters could become. On 31 May 1809 at the Lyceum we have 5 Drury Lane employees sharing a benefit night (Fig 1).

The charge was £148 2s 6d (considerably below the usual charge this season of around £220). However, the charge was not allocated equally between the five – ‘Fisher Quarter & 1/16 [5/16], Butler 1/4, Jones 3/16, Kelly 1/8, Wells 1/8’ and we have documented this in our note for this Event. We know that they had a deficiency (i.e. did not meet the charge from the door receipts) and needed to make up the balance from their ticket sales – the door took £86 6s 6d and the total tickets sold was £195 18s – but the account books doesn’t record who sold what, so it is unclear how profitable the night was for each of the five. In instances such as this, where we have no record of the breakdown of ticket sales for each individual, we have allocated the money evenly across all beneficiaries, although it is certain that there would have been considerable disparities between what each would have managed. We have divided the total number of £ equally, with any remainder being assigned to the first person in the list of beneficiaries. While this overplays the monies earned by some, and downplays those earned by others, we have at least documented that each of them participated in a financially successful benefit night, taken as a collective.

Tickets taken

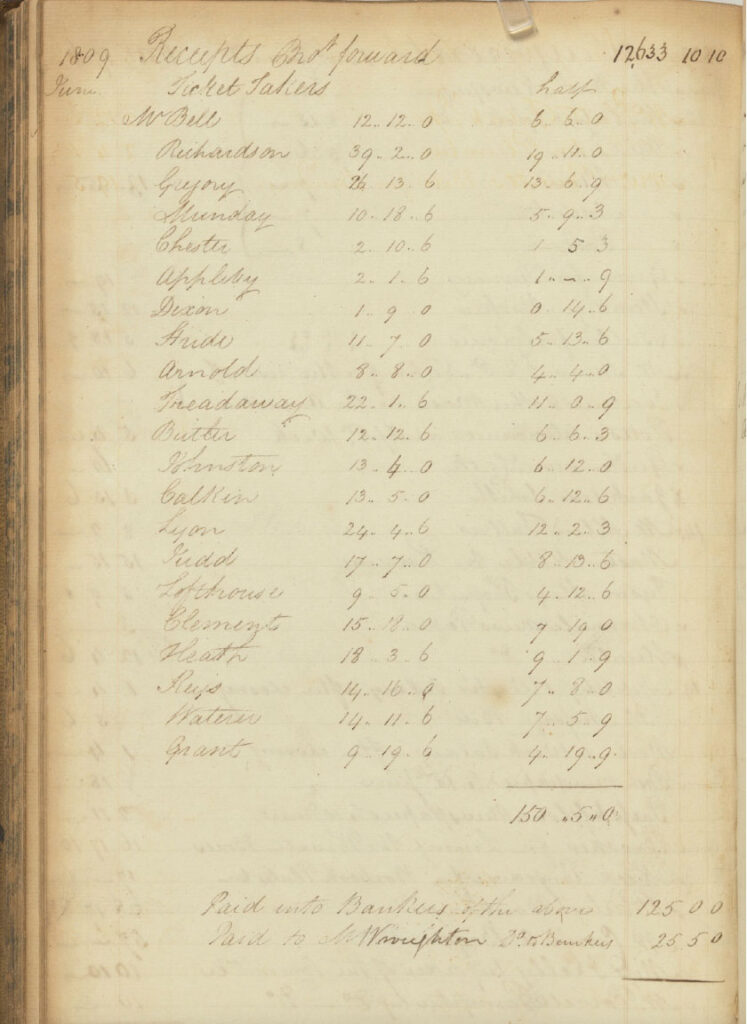

These are large group benefit nights with usually 10-16 people listed as beneficiaries, but sometimes even more. These are typically lower level employees without the status or network to warrant the prestige (or the risk) of an ordinary benefit. The key distinction here is that there was generally no charge imposed on these nights by management but management retained all door receipts and usually required a payment of half the value of the tickets sold. Thus, the reward was much reduced for those involved but there was no risk as they could not incur a benefit deficiency no matter how few audience members showed up. Audiences were indeed often sparse, with ticket nights typically held towards the very end of the benefit season when much of fashionable society had left London for the summer.

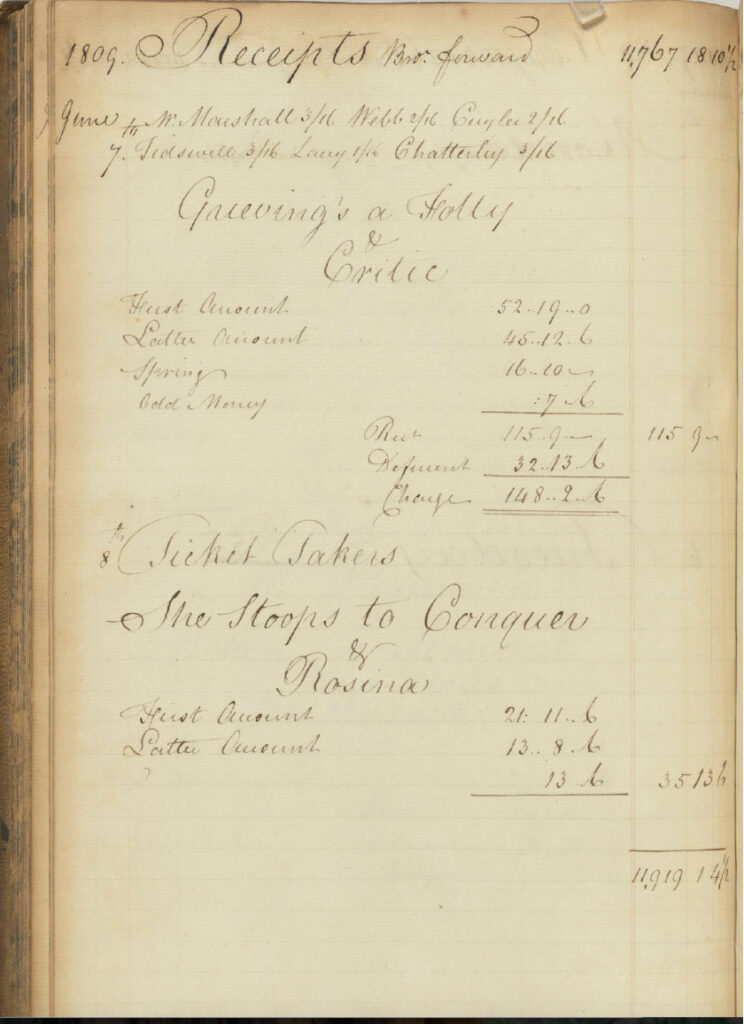

In an example from 8 June 1809, one of the final nights of Drury Lane’s season, there was a ‘tickets taken’ night for an unspecified number of individuals (Fig 2). As the only ‘tickets taken’ night that season, when the account book subsequently identifies a list of 21 ticket takers two days (but sixteen pages) later we can link these individuals to this night with the same degree of confidence that we do the tables of ticket sellers given in the Covent Garden accounts on each night (Fig 3).

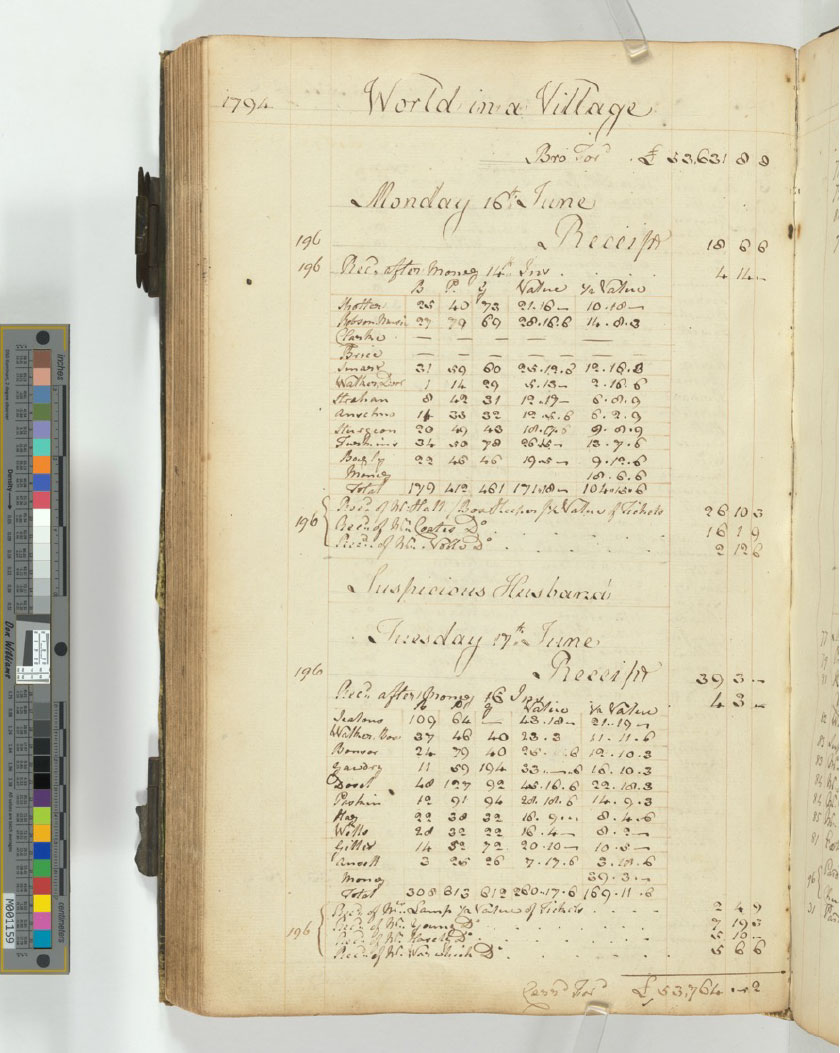

Full and half value figures are given and we record the full value to show how the night grossed as whole and so to allow more ready comparisons to other nights on which those plays were staged. Different accounting practices at Covent Garden mean that more detailed information on ticket nights is presented there, typically with breakdowns for box, pit, and gallery, as well as details of full and half value sums where applicable (Fig 4) – some employees might be granted gratis tickets, which are identified either by the annotation ‘gratis’ or by the absence of a half value calculation in their record.

It should be noted that, in some cases, the receipts within the category ‘ticket money’ – which relate to half value sums being brought in by ticket sellers – will often contradict the sums that we have allocated to each individual on a specific night (see above for our practice of dividing ticket sales between beneficiaries). Given that ticket money could often be repaid in instalments, that few indications are given for which night ticket money is paid, that we cannot be sure that ticket money is repaid in full,and that Drury Lane in particular tends to note ticket nights using the convention ‘For Fisher & Others’, without giving the names or number of others involved, trying to retrofit the ticket money delivered would be a painstaking endeavour, if not a fool’s errand. We felt it more important to document that people participated in a ticket night in so far as we are able even if the success of some (such as Fisher, who is linked to a night without the unknown ‘others’) is therefore inflated.

Charity nights

Charity nights were a regular if infrequent feature of the Georgian repertory. Charity nights were hosted by managerial fiat with an eclectic range of causes supported in the first half of the eighteenth century. However, from the 1760s, the frequency of charity nights had dwindled to 2-3 season, largely given over to lying-in hospitals in the run up to Christmas and the theatrical funds established by both theatres in the 1760s for infirm and retired employees in financial difficulties. After this period, charity nights often tended towards the patriotic, such as the benefit on 2 July 1794 for the widows and orphans from the naval battle of 1 June, which brought in £1,013 (putting Drury Lane at 166% capacity), or for the support of employees whose house burned down. Despite their charitable nature, management house charges were still levied on these nights and rates were typically higher than those given to employees, for instance we often see £84 levied against charities at Covent Garden in 1759-60 when employees were charged £64.

Benefit nights and Theatronomics

Benefit nights, particularly employee and tickets taken nights, yield highly granular data that can tell us much about managerial practice and the waxing and waning of individual careers. Furthermore, they are perhaps the richest source of data we have for many of the non-performing employees of the theatre for whom other sources are scant. Thus, we have paid particular attention to beneficiaries throughout our resource.

Rich as the data may be, it also presents challenges. For one, like many other aspects of the account books, data is presented incompletely and inconsistently over our period and there are many variations of the employee benefit night. For another, our data structure was developed before we had access to most of the Drury Lane manuscripts due to the multi-year refurbishment of the Folger Library completed in 2024. Moreover, there is a tension between recording the overall take of a theatrical evening (measuring the revenue of the theatre) and tracking the financial beneficiaries of such nights (measuring the profitability of the theatre and the financial gain of employees) that was further complicated for us by the first two issues already noted.

The main ways in which benefit nights appear in the account books and how we have treated them can be summarised as below:

- Employee benefit, named employee(s), charge, no ticket breakdown [receipts and charges documented, Event linked to named person(s) where identified, and expense payment to beneficiary documenting the balance paid to the beneficiary if the door receipts exceed the charge when such a payment is shown in the account book (as the account book does not always record payments of the surplus to beneficiaries when the receipts exceed the charge]

- Employee benefit, named employee(s), charge, ticket breakdown [receipts, charges, and ticket breakdown documented, Event and tickets linked to named person(s) where identified, and expense payment to beneficiary documenting the balance paid to the beneficiary if the door receipts exceed the charge when such a payment is shown in the account book]

- Tickets taken, named employees, everyone pays half value [tickets documented at full value and linked to the named person(s) where identified, and half value categorised in the receipts and linked to the named person(s) paying the moiety owed]

- Tickets taken, named employees, some pay half value [tickets documented at full value to the theatre’s income, and half value categorised in the receipts and linked to the named person(s) paying the moiety owed]

- Tickets taken, no employees named, total tickets only [tickets documented at full value to the theatre, generic ‘ticket takers’ record attached to the night to allow the tracing in the round of all events entered in this way, ticket money receipts may indicate some half value payments to the theatre if the date of the benefit is included in the payment narrative]

- Tickets taken, no employees named, no tickets total [tickets documented at full value to the theatre, generic ‘ticket takers’ record attached to the night]

- Employee benefit, tickets free up to a predetermined amount [benefit logged twice, firstly up to predetermined amount as per 2. and secondly as per 3. In these rare cases, the even amount (round figure ending in 0 or 5, no shillings and pence) went in full to the beneficiary, the secondary amount (with shillings and pence) was divided between beneficiary and theatre.]

Occasionally, the lines between employee benefits and tickets taken nights are blurred. For instance, 11 May 1769 saw Covent Garden stage a benefit night for Michael Stoppelaer. While it was a benefit night in the strictest sense (advertised for him, a single beneficiary), the arrangements for the house charge were more complex than usual. He was liable for half the standard charge (£31 10s rather than £63) but he also paid management half value of his tickets sold (£55 7s of the £110 14s). Thus, Stoppelaer’s night had less risk but it did cost him financially. The interesting question of whether this was a model proposed by him (to minimise risk) or management (to give him an individual benefit, but on reduced terms) requires further contextual information to determine. In our resource, we have coded all such nights – where management get a cut of the tickets sold – as a tickets taken night, even if it might be ostensibly labelled or advertised as a standard benefit night.

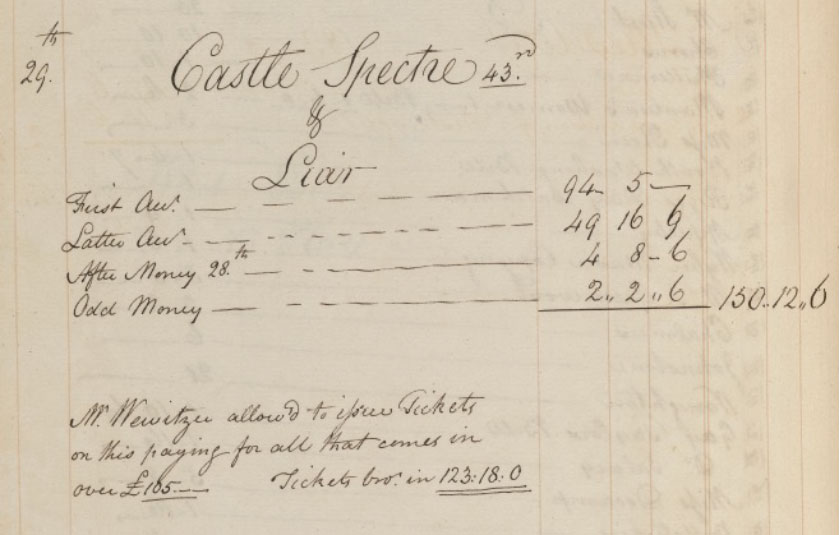

Drury Lane also began to have increasingly complex configurations for benefit nights from the 1790s onwards, likely a response to a falling uptake in benefit nights as employees didn’t want to assume the risk of ever-increasing charges. Ralph Wewitzer was one of those who had a bespoke arrangement. He had ticket nights for which he was the sole ticket seller (Fig 5). Exempt from the house charge, he was allocated a fixed value of tickets (typically £105 as on 29 May 1798) which he could sell gratis; for every ticket he went over this amount, he owed the theatre half value. In our database, he will be listed twice as a beneficiary on this date with respective amounts of £105 9 (pocketed by him in full) and £18 18s (to be divided between him and the theatre).

It should also be noted that, on rare occasion, the beneficiaries listed in the London Stage differ from the beneficiaries named in the account books. This is most common with regard to benefits shared by husbands and wives; as our focus has been on capturing information from the accounts we have attached the beneficiaries detailed there (and divided money accordingly) and added a note to the Event to record the discrepancy. A slightly more complex issue arose with instances where the London Stage gives conflicting information, such as 3 May 1766: the playbill denotes this as a night for James Perry and Michael Stoppelear, but the Public Advertiser declares it a night for John Moody, Richard Hurst, and Elizabeth Dorman. As there is no surviving account book for this season, we have linked all these beneficiaries to allow for the tracing of careers in the main but have nothing to offer to resolve this conundrum. Some charity nights will also be presented in a subtly different way in our resource than the London Stage in regard to nights for a ‘Person(s) in Distress’. Rather than creating separate profiles, we have created a single record with which all nights on which this advertising configuration was used can be associated (but the detail of the person, where available, is given in a note). It should also be noted that those in distress are sometimes also allowed to sell tickets at an employee benefit night, rather than being a sole beneficiary.

An individual career trajectory, as evidenced through the benefit system, can be traced via the People section on the site, with Person records containing financial information for all nights linked that that individual. Author and charity nights appear in a separate section from employee nights allowing, for example, a clearer sense of how Elizabeth Inchbald was remunerated for her authorial endeavours as opposed to her acting career.

Charges

Management’s accommodation of charitable, authorial, or employee rarely extended to the operational costs of opening the theatre for the night. In the vast majority of cases, the beneficiary was liable for the charge; however, that charge could vary within the same season from beneficiary to beneficiary. Moreover, the charge increased considerably over our period: we start in the 1730s with standard charges of £60 (but lower for some beneficiaries) but by the close of our period, Drury Lane is charging £200-£220 (there’s considerable variation in the later Drury Lane charges). These amounts represent only the fixed element of the charge: we also see supplementary charges introduced in the 1760s for those who wished to add flourishes to their night such as extra singers or kettle drums, usually amounting to only a couple of pounds but it could be more considerably more on some occasions. In a moment of notable managerial parsimony, Covent Garden account books show the consistent addition of a supplementary charge for candles in 1767, with beneficiaries forced to supply their own or pay a charge. For those employees seeking to improve the odds of a successful night, they might also recruit a celebrity performer to appear for them, accruing the additional costs of having to pay their fee; while such transactions are often off the books and private matters we do see some charge-related expenses where the managers make a ‘gift’ of a celebrity, paying their nightly fee on behalf of the beneficiary.

There is some evidence of how the nightly charge was calculated. Particularly informative is John Powell’s ‘Tit for tat’, a manuscript of an unprinted pamphlet attacking Drury Lane management for not promoting Powell to be treasurer of the theatre. The document, covering the period 1747-49 and reproduced in London Stage 4.1, 121-28, gives a very informative if partial commentary on the receipts and expenses of the theatre with a view to calculating the nightly charge.

There is a full calculation of the nightly charge in the Covent Garden account book for September 1760 (reproduced in London Stage, 4.2, 814-17). There is also a partial calculation in September 1758, not reproduced in London Stage. We have not found any detailed attempt to calculate the charge after this time but the nightly charge accelerated along with the expanding theatrical capacity and associated costs, often to the disgruntlement of employees. The nightly charge is an informative lens into how management conducted their business from the macro-organisational perspective, but also as to how they managed their employees on an individual level. As part of salary negotiations, some employees were given a free night (recorded in our system as a charge of £0 0s 0d, as opposed to N/A, when we have no record of the charge levied), or could even have two nights a year – one free and the other subject to a charge. Other employees, such as the example of Stoppelaar above demonstrates, could negotiate different arrangements to the standard charge.

There are peculiarities in the account books that should be flagged in relation to house charges. These are particularly relevant for Covent Garden where we have considerable periods when management does not record the house charge for benefits for nights which are evidently not clear benefits but incorporate the receipts of the evening into the running total for the season’s revenues as if there was no charge.

But it is simply inconceivable that Thomas Harris would give clear benefits to the amount of beneficiaries suggested by this practice 1786-91 and 1793-. Part of the answer surely lies in the other account books for this period now lost to us. Similarly, there are ticket money payments from beneficiaries that have unfortunately not been listed as beneficiaries for events earlier in the account books at Drury Lane (i.e. payments for no apparent cause). In sum, the recording of transactions related to benefit nights is erratic and frustrates straightforward analysis; nonetheless, they are a remarkably rich source of insight into eighteenth-century theatrical culture.

Further reading

Robert D. Hume, ‘Theatre as Property in Eighteenth-Century London’, Journal of Eighteenth-Century Studies 32:1 (2008), 17-46, 38.

Judith Milhous and Robert D. Hume, ‘Playwrights’ Remuneration in Eighteenth-Century London’, Harvard Library Bulletin 3 (1999), 3-90, esp. 50-53.