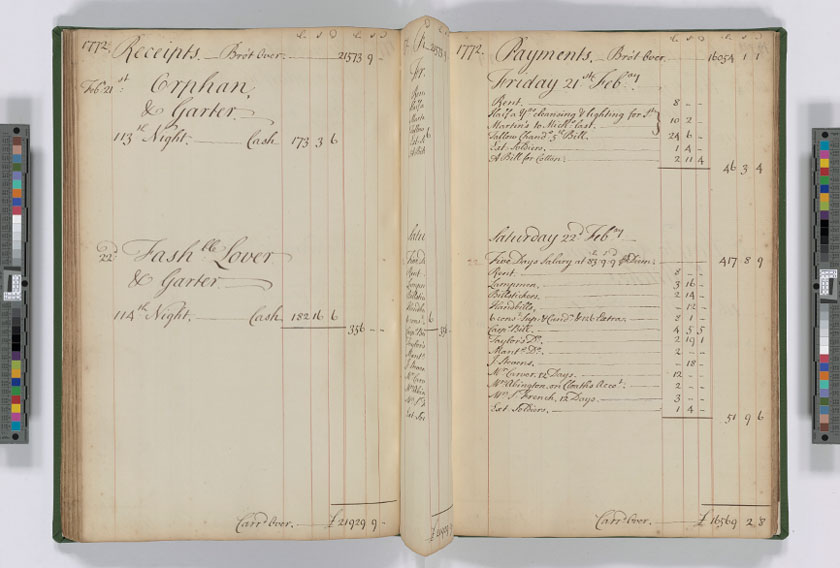

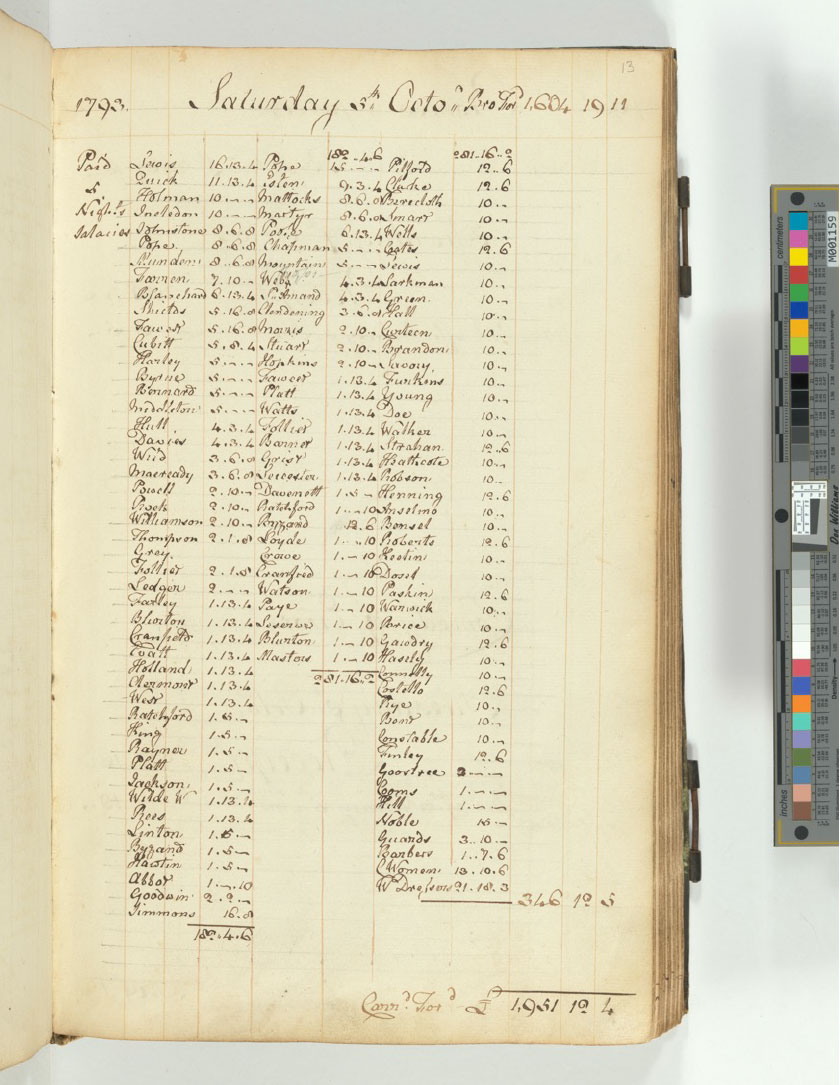

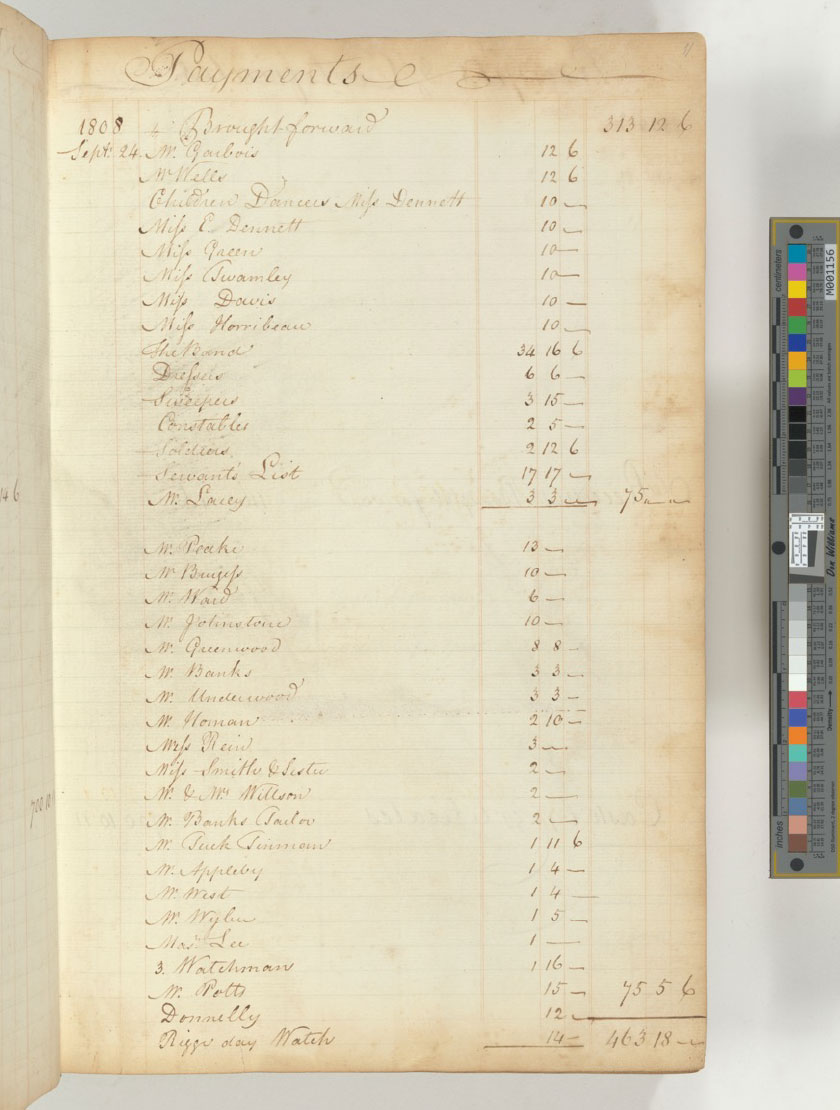

The account books give an itemised list of the theatres’ day-to-day receipts and payments, with varying levels of detail. Receipts are almost always recorded on the books’ left-hand pages, expenses on the right. When recorded before or after the theatrical season proper, they are written in occasionally dense lists, with the dates written down the side. When recorded during the season, each day on which the theatre performed is given a section spanning the manuscript opening, with a varying number of items assigned to that performance day. For most of Covent Garden’s books, each Saturday during the season has a dedicated page for the weekly payroll of employees on per-diem salaries, separate from the performance-day section (if there was a performance that day). Drury Lane, on the other hand, generally records company salaries as a collective figure, so individual salaries are largely not available, until the 1799-1800 season, from which point the account books record all salary payments amongst the regular expenses.

The increasing density of the account books, particularly around Saturday payday, reflects the theatres’ growth in size and complexity as the century progressed.

Some examples of the account books can be seen below and readers can see further examples of complexity in the Benefit nights and charges document.

For our database, we have transcribed each item of receipt and expenditure, recorded their amounts in £-s-d, categorised them, added explanatory notes where necessary, and linked door receipts (but only door receipts) to the relevant performances. The exceptions are Covent Garden’s Saturday payrolls, each of which have been treated as single, large payments, recorded in square brackets in our dataset. For two Covent Garden seasons, 1740-41 and 1746-47, we have also generated a batch of expenses not directly recorded in the books, but implied by the accounting procedures shown there. This was necessary because Covent Garden during those seasons paid something called the ‘nightly charge’ (comprising various fixed and almost-fixed payments, such as the security staff’s salaries) out of each night’s door receipts; but the account books do not show this on the expenses pages, and it must be calculated from the difference between the night’s total door receipts and the amount that reached the treasury after the relevant money had been diverted. To indicate that we have created the explicit expenditure records ourselves, we have written these in square brackets, and glossed them in the notes.

Some of the account books also include separate sections at the end, e.g. detailing the payments made to renters and the money used to pay them. Where such sections overlap with the main body of receipts and expenses in some way – e.g. if the main expenses have included generic daily payments to a ‘Renters’ account, and the section at the end of the book gives the details of that ‘Renters’ account – then the expenses in question have been recorded in a different place to the rest of the expenses, as it would distort the data to mix such records together.

Transcriptions

We have aimed to transcribe everything as it appears in the manuscripts, the vagaries of punctuation inclusive. However, this was not always possible or optimal as our primary focus was on the identification, categorisation, and the linking to people of the money documented.

We have sometimes split a complex transaction into its constituent parts or grouped salary payments t o better allocate the money to the correct person/category. Thus, for example, where a book says, ‘Properties £4 3s & House Bill 11s 11d’, then gives a total of £4 14s 11d, we separated this into two distinct expenses. Likewise, where a book says e.g. ‘Mr Jenkins £3 7s and Mrs Wright’, then gives a total of £6 8s, we made the relevant calculations and separated this into two expenses.

Our functionality for formatting was limited so please note that our transcriptions are in plain text and we could not replicate underlining or superscript. Arguably this has rendered some entries more difficult to read in transcription than they are in the account book, because, for example, ‘Coming’ is a very occasional abbreviation of ‘Commencing’ which will appear as ‘Coming’ in our transcription. Where our transcription has ever confused the account book entry, our approach compensates by contextualising it with a receipt/expense category, a payment type (for expenses), and (when appropriate) explanatory notes. It is worth noting however that the superscript conventions in the manuscript sometimes make Mr/Mrs/Ms difficult to distinguish and it is likely that there are some entries that have been misgendered (potentially misgendering some of the people we have identified and for whom we have created a record solely on account book evidence).

Similarly, the account books sometimes include calculations within entries – e.g. calculations showing how much money was owed to the Duke of Bedford, next to the monetary figure that was in fact paid him. The conventional mathematical layout of e.g. addition and subtraction sums, although used by the scribes in the account books, is virtually impossible to replicate in transcription, meaning that, in these cases too, our transcriptions may sometimes be less clear than what appears in the books. Again, though, these cases are few; we provide explanatory context; and the reader is able to view photos of the books on the Folger Library’s website or, if possible, on Gale’s database (paywall).

Explanatory notes for expenses are provided for separately to the transcription of the account book entry; however, due to a glitch in our database, the explanatory notes for income items are appended to the transcription in square brackets. For performance-related receipts (e.g. cash taken at the door,) we specify the nature of supplementary income on the night in question (e.g. ‘Odd money’, coming in on top of first account, latter account, and aftermoney takings for many of the early nineteenth-century Drury Lane performances). On very rare occasions, there are instances of Events with two entries for door receipts: this occurs when there are multiple supplementary revenue streams that exceed the number of fields we have for a single receipt.

When a transaction was recorded without a date, we used contextual evidence (previous receipt/expense, dates of receipt/expense on opposite page, or information in the prose narrative) to identify a probable date. Where we had the month but not the day of that month of a transaction, we used the 1st of that month, unless we had other evidence that made this impossible. Where we have supposed dates, we generally indicate the rationale in a note.

Categories

The financial data has been categorised to allow scholars to track the proportions of money received/spent by the theatres at the most granular level possible. We therefore designed and implemented two categorisation systems, one for receipts, one for expenses. The receipts system was simpler because the theatres’ income was relatively straightforward, consisting mostly of door receipts that can be mapped directly to an Event i.e. night of theatrical activity (~19,000 of our total ~27,000 receipts). These categories allow for detailed, nuanced analysis of the data, and allow all instances of the theatres’ most common items of receipt/payment to be grouped together. However, such granularity is unwieldy, so we have grouped these into higher level umbrella categories for ease of use e.g. Music is an umbrella category for 14 types of musical expenditure that we have found prominent in the accounts. Moreover, for expenses, there is a third type of categorisation: payment type. This divides payments between ‘internal’ (to the theatres’ employees, broadly understood), ‘external’ (to outside recipients), ‘departmental’ (to heads of departments for distribution amongst what was identifiably or probably a combination of internal and external recipients), and ‘unknown’.

Overall, our categorisation, filters, and export functionality allow the user great flexibility in exploring the data, facilitating approaches from several different angles, from the macro to the micro. In combination with the transcriptions, our resource allows the user to come up with their own configurations, their own categories, as their research needs dictate.

Assigning transactions to people

We have attached approximately 36% of (non-performance) receipts and 23% of expenditure items to a person or persons in our database.

We have focused our attention on beneficiaries (on the grounds that we have benefit night financial data already associated with them and that these people are likely to be of most interest to the theatre historian) and on the external suppliers and tradespeople to the theatres (on the grounds that a key objective of the project was to widen our understanding of the theatres’ place in the wider London economy).

We have taken an assertive approach to attaching People to income and expenditure: we have linked people to payments in many cases where we have reasonable grounds but not absolute certainty. We have also linked payments to each individual mentioned in a given entry e.g. a benefit deficiency received by a theatre might be associated with multiple individuals who shared that benefit night. While our linkages allow users to see a richer picture of an individual’s financial dealings with the theatres, we do urge care when exploring these linked transactions. In some instances, the linked person has been identified on a ‘most likely candidate’ basis; for instance, payments for “Decamp” can refer to either Maria Theresa (Miss Decamp) or Vincent (her brother, Master/Mr Decamp). In these instances, we have assigned linkages based on our wider prosopographical research, rather than the gender given, or hinted at, in the account book entry. Consequently, some payments recorded for ‘Mr’ may be linked to a woman, and those for ‘Mrs’ to a man, where we feel the manner in which a payment has been recorded, or has been transcribed, suggests that an alternative association is more likely. To take an illustrative example, Willam Egan dies in 1785, but a ‘Mr Egan’ continues to appear in the account books’ lists of beneficiaries at Covent Garden through into the 1800s. There is, however, only one ‘Egan’ known to be at Covent Garden after that date and it’s his wife, Elizabeth, who is the wardrobe keeper (and later costume designer). Thus, the entries for these years read ‘Mr Egan’ ‘Mrs Egan’ and ‘Egan’ (but never more than one of these in a season). There are also corroborating entries on the expenses side: “Mrs Egan for Women Dressers and Bills” is a stock entry (so to speak), but sometimes it’s entered as “Mr”. Therefore, we linked all of benefit nights for ‘Egan’ and ‘Mr Egan’ to Elizabeth on the basis of activity dates, gaps in her record, the pattern of shared benefits, corroborating expenses entries, and a lack of other Egans known to be active at our theatres in that period. We attribute the occasional ‘Mr Egan’ in these beneficiary lists to scribal error.

Further issues

Users should beware that the neat visual presentation of categorised data belies the many underlying challenges in comparing the inconsistent records of Covent Garden and Drury Lane.

We have designed and implemented a system that incorporates data spanning over eight decades, and numerous different accounting and scribal practices across two theatres. Some of the account books are explicit and detailed about expenditure, others less so; some account books mention payments to certain departments, and give no indication as to what it was used for within those departments; some account books record daily payments to kettle drummers, and frequent payments to organists, bagpipers, etc., while others do not; each of these account books was only one element of a larger accounting system, comprising a number of other books that mostly no longer survive; and the exact place and role of each account book within that system, e.g. how much of the theatre’s total expenditure it actually covers, differs from book to book.

There are especially marked differences between Drury Lane’s and Covent Garden’s books, which frustrate attempts at direct comparison between the theatres.

Moreover, some theatrical business was conducted privately by the theatre’s proprietor out of (or into) their own pocket; Thomas Harris (owner and/or manager, 1767-1820) seems to have had a very busy private account used for Covent Garden business, and, although he recouped the relevant expenditure from the theatre’s treasury, and paid the relevant receipts on to it, the account books’ records of such transactions are highly obscure, and it is doubtful that there was a perfect reconciliation between Harris’s account and the theatre’s. The theatres, especially Drury Lane, also set up supplementary funds concerned with particular areas of activity, or as sinking funds; or became overdrawn with their bank; or operated through trusts and trustees; all of which activity, happening at least one remove from the theatre’s main treasury, is represented only hazily, or not at all, in the account books.

There is also the issue of timeframes: some account books begin their records at the start of the season, some a few weeks or even months beforehand; some finished fairly soon after the season ended, some went on for many pages, and even included payments whose dates fell within the following season, or even years down the line, rather than including those payments in the following season’s or seasons’ account books; and if it might be speculated that this was because the payments in question related to the season in whose book they were recorded, it should be noted that the books often included payments for services or goods rendered the previous season, or many seasons previous.

The categories we designed were therefore determined, to a large extent, simply by what was visible in the account books; and they were designed to strike a balance between being flexible enough to incorporate the sorts of receipts/payments recorded in account books from different theatres and different decades, and being specific enough to capture, and portray, recurrent items of receipt/expenditure even when they were explicitly recorded only or mostly at a single theatre, or only or mostly in a certain decade. Thus, our multi-tier system allows, for example, Drury Lane’s frequent records of in-house mantuamaking payments to be captured in the category of ‘Mantuamaking’, but, even though Covent Garden’s account books gave virtually no corresponding records, the two theatres can still be compared in terms of umbrella categories: the payments categorised as ‘Mantuamaking’ are found in the ‘Clothing’ umbrella category, and the total amounts spent on ‘Clothing’ at the two theatres can then be compared. What can also be compared is how each theatre allocated its funds within the higher-level umbrella category: the disparity between Drury Lane and Covent Garden’s records of mantuamaking becomes no longer an obstacle to analysis, but an object of analysis in its own right.

In the end, then, our data gives not just a picture of the theatres’ financial activities, but a picture of how the theatres recorded those activities.

Admittedly, the two different pictures compromise rather than complement each other: inasmuch as the data shows how the theatres recorded their receipts/expenditure, it obscures how the theatres received/spent their money; inasmuch as our categories attempt to encompass and reconcile divergent recording practices so as to show, in an absolute fashion, how the theatres received/spent their money, they obscure how the theatres recorded their receipts/expenditure. But this problem is an inevitable consequence of categorisation. For all the caveats, we believe that our database has produced some powerful, nuanced and fascinating results.

Nonetheless, it is essential that users are aware of why and how the data differs from theatre to theatre, and decade to decade, in the way that it does, and understands the nature of the multi-tier categorisation.