Determining the evolution of theatre capacities across our period is a very difficult business. Various numbers have been proposed for different periods of the century, often on patchy evidence, and these numbers do not necessarily synch up neatly with each other. These numbers are often speculative, particularly with regard to the divisions between box, pit, and galleries (BPG). Theatre historians have been cagey at times about such matters: Charles Beecher Hogan, for example, in his excellent introduction to Part 5 of the London Stage, 1660-1800 (covering 1776-1800) is happy to give the capacity of Covent Garden in 1782 when it was rebuilt but is rather silent on what it was in 1776 (5:1, xliii).

Such caginess is warranted. Individual seats were a rarity and theatregoers usually sat on benches on which no fixed number of people could be said to fit. Nor was the audience stationary or constant in number throughout the performance. Prior to the 1760s, theatregoers could sit on the stage on benches or in makeshift boxes. Theatre managers maintained free lists and members of the company could issue ‘orders’ or free tickets – practices that were sustained throughout our period – but theatres were not assiduous about recording those numbers. Theatregoers came and went, typically after the first 3 acts when the half-price entrants could come in and some, eager to see the afterpiece at the other house, might then leave. Renters – de facto shareholders – would take the free seats they were entitled to on any performance night but we rarely have records of how many were there on a given night. Biographical descriptions of big command or benefit performances make clear that the theatres would often cram the theatre well beyond what any official seating capacity might assert.

Making a claim that such or such a figure is the headcount capacity of a theatre in the eighteenth century is a fool’s errand. What is clear – due to half-price entry, the free list, orders, and renters in the main – is that the theatres would generally always be busier in terms of headcount than the receipts would suggest.

Previous figures supplied by the various editors of the London Stage and other well-established sources for the period are used widely by theatre historians. However, there are issues with some of these. There has been, in our view, a misreading of records of benefit tickets sales. Theatre historians have looked to these to determine maximum capacity as they tended to be the bigger nights of the season. However, benefit tickets sold does not equal the number of people in the theatre; it seems overwhelmingly the case that, like modern airlines, tickets were sold in the safe knowledge that some punters were happy to support a beneficiary but would not turn up. More importantly, tickets for certain parts of the house were oversold in the knowledge that customers would spill over to other parts of the house e.g. late-coming pit ticket holders would end up in the galleries. Beneficiaries also sold tickets on credit and were sometimes never paid. Another significant issue is that careful scrutiny of the receipt figures for the period have flagged moments of minor seating expansion which do not feed into our current understanding of seating capacity.

A different approach is thus warranted.

Our concern being the business of theatre, we are less interested in how many people were in the theatre than with the revenue generated. We are primarily interested in generating a metric that allows us to broadly trace the financial performance of a theatre or a Work across the period that takes account of the changing size of the theatres.

While there is a clear corollary between actual headcount capacity and revenue, theatre managers in our period were, like us, less concerned with how many people sat in the theatre than they were with the revenue generated and theatre aficionados as this quotation from James Boaden shows often configured theatre size in terms of revenue: ‘The size of the theatre will be known, when I say that it holds 520l., at 5s. for the boxes, and 3s, for the pit’ (Boaden, I:xx). There are plentiful statements prioritizing revenue over headcount like this in the record during our period. Moreover, we look to prompter Richard Cross whose estimates of theatre attendance were formulated in pounds, rather than headcount, for further validation of this approach.

Thus, our capacity figures are understood in terms of revenue. We supply the underlying division of box, pit, and galleries when we have a reliable source but we do not offer headcount estimates when we have no evidence of the nature of the changes that bring about an increase in revenue. Moreover, we should be very clear that our revenue capacity figures do not equal the maximum revenue actually possible on a given night; rather, the figure given should be understood as a full revenue take on an ‘ordinary’ night. The relationship between revenue and actual headcount is further complicated by the half-price system – it is perfectly possible for a theatre to take in more money with fewer people depending on the distribution of full-price and half-price customers. On some occasions, such as benefit nights or command performances or highly anticipated new plays, the revenue generated will exceed our figure as higher prices can be charged and traditional seating arrangements disrupted (e.g. pit laid into boxes) or, as previously stated, more tickets will be sold than people will actually come. Perhaps most pertinently, to be present at such key events, people were clearly prepared to squeeze onto the benches as many colourful contemporary accounts testify. And, given the voluminous dresses of the period, the proportion of women in an audience also played a part in how much squeezing might be required – or was possible.

However, as we are interested in giving a balanced view of the whole repertory, across seasons and across an individual season, we believe that were we to peg our capacity revenue figure to such outliers, it would badly misrepresent nights with lower receipts as being less successful than they would have been perceived to be by theatre management.

The consequence of this is that the database will show nights where capacity is >100%; we believe such results will be helpful in identifying the sometimes extraordinary effect of a command performance, a highly touted benefit night, a hotly anticipated debut, or a much lamented farewell performance.

Methodologically, we have started from the current capacity figures from the London Stage, the views of other theatre historians, and modified these with some additional evidence from newspapers. We have then evaluated these numbers against the revenue figures in extant account books. We have looked at the highest dozen or so figures for nightly revenues in each season and, downplaying outliers, have settled on a capacity revenue figure that would accommodate those receipts. Of course, we are on shakier ground in the pre-1766 period when we rely on estimates for many seasons at Drury Lane and have much more sporadic receipt data across both theatres.

In brief, our capacity revenue figure is generated from a comparative account of established theatre capacity figures and the actual door receipts where extant; in the end, we offer figures that we believe the treasurers of the theatres would have been satisfied with as a full house. But these figures are derived from informed speculation and should be treated with caution: rather than providing definitive conclusions on theatre capacity in terms of headcount, they are primarily intended for use as a tool to assess the comparative financial performance of the patent theatres.

They may also be useful as a mechanism to compare the relative popularity of a play at different periods of the long eighteenth century as the theatres increased in size.

We present below a table of the changing revenue capacities for both theatres 1732-1809 accompanied by a brief explanatory narrative. Where it makes sense to consider different periods collectively, we do so and explain why. We round our figures up to the nearest £10 for ease and as implicit concession that these figures are approximate. Where we have precise BPG figures from theatre historians that look reasonably correct, we include them as given; the spareness of the table indicates the paucity of robust figures. The years in the table indicate the years in which the theatrical season began and ended i.e. 1732-1759 refers to 1732-33 to the 1758-59 seasons inclusive. The figures take into account the change in ticket prices in 1792 from the 5s to 6s scales: 1746-1792 Box (5s) Pit (3s) 1st Gallery (2s) 2nd Gallery (1s) ; 1792-1809 Box (6s) Pit (3s 6d) 1st Gallery (2s) 2nd Gallery (1s).

We have made efforts to accommodate periods when companies acted at different venues due to reconstruction or fire but, as we are unable to apply two different capacities to a single season, the calculations for Drury Lane in 1808-9 will not be accurate for Events staged at the Lyceum Theatre where the troupe played after their building burnt down on 21 February 1809.

Covent Garden

| Revenue (£) | Box | Pit | Gallery (L) | Gallery (U) | Total | |

| 1732-1759 | 190 | |||||

| 1759-1766 | 220 | |||||

| 1766-1776 | 240 | |||||

| 1776-1782 | 290 | |||||

| 1782-1792 | 340 | 729 | 357 | 700 | 384 | 2170 |

| 1792-1793 | 450 | 850 | 632 | 900 | 180 | 2562 |

| 1793-96 | 460 | 850 | 632 | 900 | 361 | 2743 |

| 1796-1803 | 500 | 1000 | 632 | 900 | 361 | 2893 |

| 1803-1808 | 530 | 1200 | 632 | 820 | 361 | 3013 |

| 1808-1809 | 400 | 900 | 800 | 800 | 2500 |

1732-1759 (£190)

London Stage (3:1, xxxi-xxxii) suggests a capacity of 1413 (240-498-450-225) while Pedicord (1954) suggests 1335. Brayley states that the house was ‘calculated to produce about 200l. nightly (13). Based on receipt data from Rich’s Register and from the Covent Garden accounts for 1735-36, we believe that Brayley and the London Stage are closest. Although the London Stage BPG figures are substantiated by thin evidence (and thus excluded from our table), when they are multiplied by the relevant ticket prices we end up with £191 which looks reasonably in line with extant receipt data. We round to £190.

1759-1766 (£220)

Here we have our first significant stumbling block. Although there are no records of structural change to Covent Garden and no ticket price increases, door receipts do increase noticeably in this period to the extent that the £190 figure looks outdated. There are several nights with receipts in excess of £200, with a figure of £242 for a command performance of 1 Henry IV and Love à la Mode in December 1760 the highest reached. While it must remain a possibility that the theatre business was simply becoming generally more lucrative, this reading would suggest that no night in the five seasons for which we have records in the 1732-1759 period reached anywhere near capacity. This, in our view, is much less likely than some tweaking to seating arrangements not considered sufficiently noteworthy to document. We believe a figure of £220 is representative of what would be considered a financially satisfying full house in this period.

1766-1776 (£240)

Although theatre historians have not recorded any structural changes to Covent Garden and ticket prices remain constant, we have once again a noticeable increase in door receipts. It is difficult to attribute this to any other cause than some internal changes/expansion in seating. With multiple nights in 1766-67 and subsequent seasons in the £220-250 range with some outliers above this, we believe £240 to be a more accurate ‘full house’ target for Covent Garden management at this time.

1776-1782 (£290)

Drury Lane was extensively refurbished in 1775; given the duopolistic nature of the winter theatre season, we may speculate that Covent Garden responded to some degree and this may help explain another rise in the level of receipts to £290 from the 1776-77 season onwards.

1782-1792 (£340)

Covent Garden underwent significant redesign and expansion in advance of the 1782-83 season. The Morning Chronicle (24 September 1782) stated, ‘The theatre is so considerably augmented that we take for granted the receipts on a full night cannot be less than £80 more than the house formerly contained.’Hogan claims that the new capacity was 2500 but does not justify this figure (London Stage 5:1 xliii). Sheppard simply quotes Saunders’s Treatise, which calculated the new capacity at729 in the boxes, 357 in the pit, 700 in the first gallery and slips, and 384 in the upper gallery: a total of 2170. These figures, when multiplied by known ticket prices, generate a putative revenue of £325.

The highest door receipts for this season were £340 19s 6d (a command performance of The Maid of the Mill and The Commissary on 2 October 1782). There are only a couple more receipts in excess of £300 for this season (although there are more, of course, in subsequent seasons) but – perhaps in a small breach of our methodology – we should acknowledge the ‘Siddons effect’ of her reappointment as the leading lady of Drury Lane, which doubtless adversely affected Covent Garden’s receipts. Moreover, there are some extraordinary outliers in subsequent years – command performances that generated, for example, £409 (13 January 1790) and £393 (29 December 1793) – such that we cannot dismiss the £340 figure for October 1782 as we may have done with other outliers. In addition, the success of Thomas Holcroft’s The Road to Ruin (1792) does establish that receipts of £340 were achievable for a standard night.

1792-1793 (£450); 1793-96 (£460); 1796-1803 (£500); 1803-1808 (£530) 1808-1809 (£400)

The interior of Covent Garden Theatre was entirely rebuilt for the 1792-93 season increasing capacity, according to Hogan, to 1200-632-820-361 for a total of 3013 (LS 5:3, 1473). There was also a price increase so tickets now operated on a 6s scale. Using these figures, the theatre would theoretically be able to generate £570 on a full night.

Unfortunately, the receipts do not bear this claim out. On closer examination, it turns out that Hogan has not cited his source correctly: Brayley’s figures were from a description of Covent Garden when it had burnt down in 1808, not Covent Garden as it was built in 1792 (Brayley, 15). It appears that Hogan had incorrectly assumed that these capacities were the same.

However, newspaper evidence indicates that there was a gradual development of Covent Garden’s capacity to the 3013 figure. And if we take this figure as being authoritative for 1808, we can retrofit a figure for 1792, if we consider the different capacities within 1792-1808 collectively.

The Times (13 September 1803) reports enlargements for the start of this season: ‘All the front boxes on both tiers have been enlarged by the addition of one seat capable of accommodating each with ease, six persons more than they held last season. The slips, or rather the side continuation of the two shilling gallery to the stage, are now converted into boxes. The frontispiece has been raised ten feet, and sixteen private boxes have been added, to which there is an entrance from Bow Street.’ However, while there would have been physically more people in the theatre, the additional private boxes were paid in advance and so we wouldn’t expect to see that element of the structural changes increasing nightly revenue. If we were to allow 10 people per private box, that gives us 160 people not generating door receipts. Sheppard’s description of Holland’s design is a little unclear but this text and Holland’s drawings for his building suggests that 14 boxes were enlarged as described above (91, Plate 44) and 6 more people per box gives us 84 additional revenue generating box seats from 1803. We also need to allow for the small loss of income from the 2s gallery. The implication of all of this is that the theoretical full house for Covent Garden of £570 should in fact be closer to £525 (rounded to £530) for 1803-1808 (taking out the income from private boxes) and £500 for 1796-1802 .

The Evening Mail (12-14 September 1796) gives quite specific information about previous changes: ‘Three rows are added to seven of the center boxes in the second and third tiers, which will accommodate about 150 persons more than last season. This addition will, when the house happens to be quite full, produce between 40 and 50l.’ (150 additional people at 6s/ticket comes to precisely £45). This suggests that for seasons 1793-1796 a full house would reach a figure of £455 (rounded to £460).

Finally, manager Thomas Harris’s decision to increase prices and not to open with an upper 1s gallery in 1792 had sparked public outrage to which he had to partially back down. He conceded to incorporating a 1s gallery and built a temporary structure that opened on 1 October. The permanent upper gallery was not complete until the following season when the Morning Post (13 September 1793) reports ‘This addition, while it accommodates the Public, will increase the receipts of the house considerably’.

Therefore, if we assume that the 1792-93 season only operated with 25% capacity in the upper gallery and that the figures given by Brayley for 1808 are accurate, we can hazard that the 1792-93 season would be full at £445 (rounded to £450). Admittedly, this does not sit well with the claim of the Morning Post (£10 hardly being a substantial increase) but it may imply that it was understood that the theatre was very capable of packing more customers in that section as required.

Nonetheless, our methodology is certainly strained in this period. The outbreak of war with France and the political affiliations of Drury Lane meant that command performances at Covent Garden, seen as the loyalist playhouse, were numerous through the 1790s with up to 16 in some seasons. The implications of this are that such nights might be considered as more integral to the normal pattern of the theatre’s repertory rather than the exceptionalism with which we have hitherto treated them. The highest revenue on a non-command night in 1792-93 is £361, for instance. Moreover, the onset of ‘Bettymania’ (child prodigy actor William Betty) produced anomalously large revenue figures for both theatres. He generated Covent Garden’s biggest non-benefit night in its history – £637 7s 6d – when he debuted as Romeo on 7 February 1805, alongside a raft of other nights in the region of £600 and more Finally, we must also recognise that we need to ‘negotiate’ our way to the final capacity figures: the figures we worked back from (1200-632-820-361) are probably the most robust of our period.

1808-9 (£400)

Covent Garden Theatre burnt down on 20 September 1808 but the troupe were able to perform at the King’s Theatre, Haymarket for the remainder of the season, beginning 26 September. We have therefore made a calculation as to capacity for this season based on this venue. Price, Milhous, and Hume estimate a capacity of approximately 2,500 after alterations in 1796 based on a contemporary source that gave a BPG split of 900/800/800 (571). Assuming ticket prices stayed the same and the gallery tickets were priced for the second gallery, this split gives a total of £450 Early performances, energised by public sympathy for the company, drew big receipts of over £450 (peaking at £488 for 3 October), but these settled down considerably. Some nights in December also just breached the £400 mark so we believe this is a fair estimate of a full house.

Drury Lane

| Revenue (£) | Box | Pit | Gallery (L) | Gallery (U) | Total | |

| 1732-1747 | 150 | |||||

| 1747-62 | 200 | |||||

| 1762-75 | 260 | |||||

| 1775-83 | 280 | |||||

| 1783-91 | 290 | |||||

| 1791-1793 | 465 | |||||

| 1793*-1797 | 610 | |||||

| 1797-1806 | 630 | 1828 | 800 | 675 | 308 | 3611 |

| 1806-1809 | 650 |

*Theatre opened in March 1794 (of the 1793-94 season)

1732-47 (£150)

Avery estimates capacity in c.1700 at a minimum of 663 although he is tentative (LS, 2.1 xxv). This is subsequent to Christopher Rich increasing the size of the pit and adding some boxes in 1696 (Sheppard, 42, 45). However, we are reliant on the receipts for the season 1742-43 as our best source to estimate the capacity from 1732. Helpfully, this season was also Garrick’s impressive debut season so we can have a high degree of confidence that the revenues generated on large receipts night were at or very close to full capacity. On this basis, we believe £150 is an appropriate figure. Using Avery’s figures as a base, we speculate that a capacity of 1000 for 1732 is about right.

1747-62 (£200)

David Garrick’s managerial tenure at Drury Lane began in 1747 and saw no fewer than nine instances of improvement works carried out, sometimes aesthetic, sometimes structural. Prior to the opening of the 1747-48 season, Drury Lane underwent renovations that expanded the first gallery (LS, 4:1, xl). The receipts we have for a portion of the 1749-50 season suggest that more substantial reseating might have taken place as £200 represents a full house. Cross notes receipts as much as £350 in his diary but he has a tendency to overestimate when the house is full (based on a comparison between his numbers and actual receipts we have from the account books for 1749-50). These exceptional receipts also relate to benefit nights so he is perhaps including tickets sold to non-attendees in his estimate.

1762-75 (£260)

Substantial renovations again took place in the summer of 1762 with pit and boxes enlarged, both galleries being rebuilt and expanded, and slips on both sides converted into boxes (in order to accommodate those who would have previously sat on the stage): ‘it is computed …that the house will contain 90l. more than heretofore’ (Lloyd’s Evening Post, 2 August 1762). Our view is that £260 maps on well to the evidence of receipts from the 1766-67 season (indicative BPGG: 600-500-300-300=1700)

1775-83 (£280)

Robert Adam carried out a major refurbishment of the theatre in summer 1775 to the tune of 4,000 guineas (£4,200) but the descriptions suggest that these were geared more towards the aesthetic than functional (LS, 4:1, xli). Stone offers a figure of 1800 capacity but doesn’t offer any supporting evidence (LS, 4:1, xl). The receipts indicate that £280 would indicate a full house, a small increase on the previous period that would both point to a modest increase in capacity resulting from the works.

1783-91 (£290)

Carter suggests that the theatre held 2000 prior to its rebuilding in 1793; Hogan puts it at 2300 (Carter 200; LS 5:1 xliii). Neither figure is supported by convincing evidence. There is evidence of refurbishment, but the receipts demonstrate that it was largely aesthetic rather than structural even if a small increase in the capacity is warranted to £290 (Sheppard, 48-9). However, there are a couple of Siddons-inspired outliers that must be acknowledged, especially Jane Shore on 21 March 1791 which took in £337 7s 6d, the largest door receipt 1776-91.

1791-93 (£450)

These two seasons are problematic with performances largely staged at the King’s Theatre, Haymarket up to 25 January 1793. From 26 January, the DL company alternated between the two Haymarket theatres: at King’s Theatre when the opera company wasn’t performing, then at the Little Haymarket when it was (i.e. Tuesdays and Saturdays). They charged the 6s scale when they performed at King’s, but reverted to the 5s scale when at Little Haymarket, which they seemingly claimed was because they were only following the pricing practices of the theatres they performed at: ‘Half Price not being taken at this Theatre, the performances will be reduced to the old established prices. / Boxes 5s. …” (Public Advertiser, 26 Jan 1793). The expenses were considerable, so ticket prices were raised to 6s-3s 6d-2s despite much grumbling from the public (LS 5:2 1377-9). The King’s Theatre could hold at least 2,500 people (as documented in LS for the performance of 7 January 1792 which took £437) and the receipts suggest that £450 represents a full house. We should note the command performance of 4 January which took in a spectacular £582 8s 6d, the largest door receipt of the company’s time at the King’s Theatre.

1793-97 (£610) 1797-1806 (£630) 1806-9 (£650)

The new Henry Holland designed Drury Lane opened its much-expanded doors in March 1794. Capacity is documented in LS at just over 3,600, a number, presumably, taken from the 3,611 figure (1828-800-675-308) given in The European Magazine in 1806 although this is stated as being an estimate (LS, 5.1, xliv; European Magazine,169). Sheppard cites a manuscript source which puts it at 3,919 although he also notes that the size of Holland’s theatre was often exaggerated (52). Moreover, the widely accepted figure of 3,611 for 1794 does not take into account some structural changes which took place in 1797 noted by Sheppard (56-7). He notes several refurbishments, related to aesthetics and access (with uncertain implications for capacity) but does record the addition of six new orchestra boxes to which we might conservatively assign 60 seats or ~£20. Further changes were made to the pit floor and additional seating was introduced on either side of the orchestra in 1806 but the precise impact of these on capacity is unclear (Sheppard, 57). Conservatively, we assume that the changes would not have been made without at least a financial benefit of £20. As these improvements were made after the European Magazine estimate, capacity then likely exceeded 3,611 from September 1806.

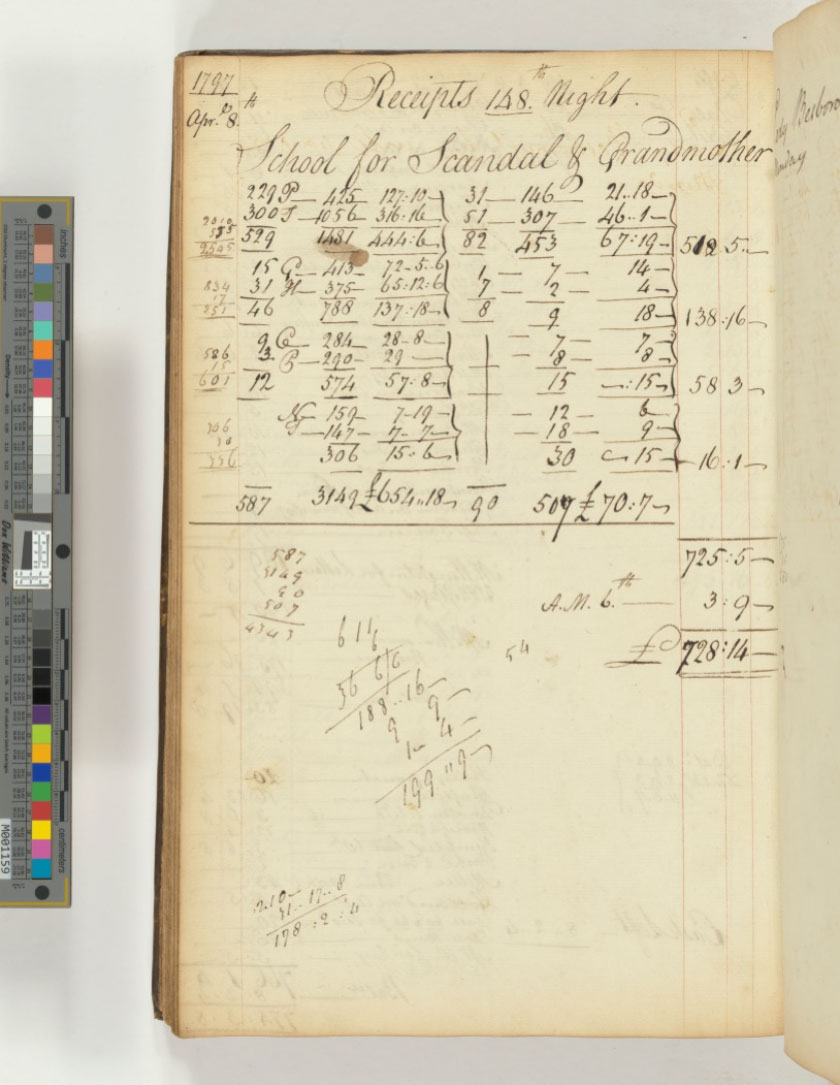

When Drury Lane reopened, the ticket prices instituted while the troupe operated at the Haymarket were also retained (6s-3s 6d-2s-1s). At these prices, the European Magazine capacity would generate a total revenue of £771. This was a financial ceiling that was never in danger of being actually hit (at least on non-benefit nights) but uniquely for this period, we have tally sheets that confirm that the notional headcount capacity could be exceeded. Take, for example, the performance of The School for Scandal and My Grandmother on 8 April 1797 which took in £728 14s 6d. This was the biggest house in Drury Lane’s history to this point, occasioned by the farewell performance of Elizabeth Farren (Fig 1; note that the apparent 6d discrepancy between the total on this image and that given above is because the aftermoney shown in the image is for the night before. The actual aftermoney [£3 14s 6d] for the Farren night is recorded on the following night, as per typical accounting practice in these books). Thanks to a tally sheet for the season (precise headcounts exist for the first decade of the 1800s as well as a couple of seasons in the 1790s), we know that Farren’s night was remarkably well attended: first account Box (1481), plus Free Box (529); Pit (788), plus Free Pit (46); F. Gall (574), plus Free F. Gall (12); and U. Gall. (306) [total 3736]. We also have a second headcount for the latter account i.e. half-price entry: Box (453), plus Free Box (82); Pit (9), plus Free Pit (8); F. Gall (15); and U. Gall (30) [total 597]. If we just take the box figures, we have 2010 people notionally in the boxes when the curtain goes up and, during the course of the evening, another 535 also elbow their way into them.

We have no way of knowing how many people would have exited to accommodate the later entries (one assumes there were some but the half-price pit figures suggest only a very few on this special night) but the point is that the notional capacity of 3,611 in which we have a reasonable degree of confidence bears little relationship to the actual amount of people that could be crammed in but, equally, the theatre – according to extant records – never reached the giddy heights of its theoretical financial full house.

The pattern of Drury Lane receipts over the period 1794-1809 is generally well below what the notional capacity suggests. However, as the 1804-5 season (when William Betty played) demonstrates clearly, strong receipts could be attained at that house. And the figures from the European Magazine are an important indicator. We therefore believe that our figures of £610, £630, and £650 are a fair representation of what Dury Lane management would have considered a full house in financial terms.

Finally, please note that the capacity figures for Drury Lane in the 1808-9 season will only hold for all Events staged before it burnt down on 21 February 1809.

Bibliography

Morning Chronicle

Morning Post

The Times

‘Andrew Cherry, Esq. of the Theatre Royal Drury Lane’, The European Magazine, and London Review (March 1806), 167-70.

James Boaden, Memoirs of the Life of John Philip Kemble, Esq., 2 vols (London, 1825).

Edward Wedlake Brayley, Historical and Descriptive Accounts of the Theatres of London (London, 1826).

Rand Carter, ‘The Drury Lane Theatres of Henry Holland and Benjamin Dean Wyatt’, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 26 (1967), 200-16

Charles Beecher Hogan, ed. The London Stage 1660-1800: Part 5: 1776-1800, 3 vols(Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1968) .

Richard Leacroft, The Development of the English Playhouse: An Illustrated Survey of Theatre Building in England from Medieval to Modern Times (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1973).

Curtis Price, Judith Milhous, and Robert Hume, Italian Opera in Late EIghteenth-Century London, Volume 1 The King’s Theatre, Haymarket 1778-1791 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995).

George Saunders, A Treatise on Theatres (London, 1790) .

Arthur H. Scouten, ed. The London Stage 1660-1800: Part 3: 1729-1747, 2 vols(Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1961).

F.H.W. Sheppard, ed. Survey of London: the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, and the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, Volume 35 (London: The Athlone Press, 1970).

Leo Shipp, ‘Charles Fleetwood, the 1744 Drury Lane Riots, and Pricing Practices in Eighteenth-Century British Theatre’, Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 47.4 (2024), 405-24.

George Winchester Stone Jr., ed. The London Stage 1660-1800: Part 4: 1747-1776, 3 vols(Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1962) .

William Van Lennep, Emmett L. Avery and Arthur H. Scouten eds. The London Stage 1660-1800: Part I: 1660-1700 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1965).