This page offers a variety of supplementary financial information that we felt could not be sensibly or successfully incorporated into our main dataset. Brief introductions to each of these sources include a rationale for these decisions. Nonetheless, these sources provide valuable insight into the operations of the theatre, particularly the day-to-day financing of the business. Consolidated receipts and expenses spreadsheets are also offered here for user convenience.

Covent Garden

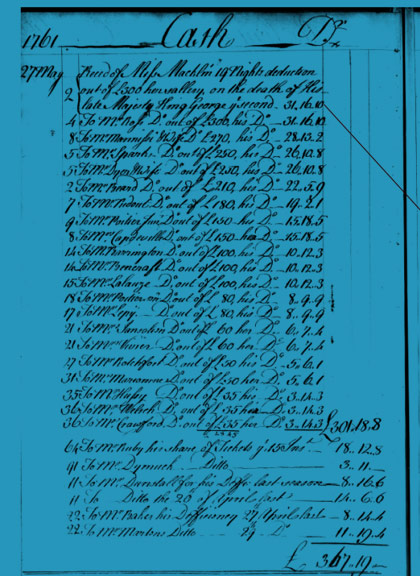

Two account books survive for Covent Garden’s 1757-58 season: one is held at the Hugh Owen Library, Aberystwyth University, GB 982 GP/2/6, the other is BL Egerton 2270. Terry Jenkins compares and analyses them in ‘Two Account Books for Covent Garden Theatre, 1757-58’, Theatre Notebook 70 (2016), 109-25. They differ markedly, especially in that the Egerton book includes a great deal of putative daily transactions – apparently based on some notion of the theatre’s average daily running costs – whereas the Aberystwyth book seems to observe only actual transactions (as most account books for other seasons seem to do, and as we would hope and expect from all of them). These differences in procedure result in significant differences even in content, especially on the expenditure side.

We have followed Jenkins in privileging the Aberystwyth book, the expenses and receipts from which will therefore be found in this resource’s main datasets (although where the Egerton book provides information on benefit night takings not found in the Aberystwyth book, we have included that Egerton information in our main datasets, too). The Egerton receipts and expenditure have been recorded as ancillary datasets. This is the expenses dataset only; receipts are recorded separately.

Download Data

Two account books survive for Covent Garden’s 1757-58 season: one is held at the Hugh Owen Library, Aberystwyth University, GB 982 GP/2/6, the other is BL Egerton 2270. Terry Jenkins compares and analyses them in ‘Two Account Books for Covent Garden Theatre, 1757-58’, Theatre Notebook 70 (2016), 109-25. They differ markedly, especially in that the Egerton book includes a great deal of putative daily transactions – apparently based on some notion of the theatre’s average daily running costs – whereas the Aberystwyth book seems to observe only actual transactions (as most account books for other seasons seem to do, and as we would hope and expect from all of them). These differences in procedure result in significant differences even in content, especially on the expenditure side.

We have followed Jenkins in privileging the Aberystwyth book, the expenses and receipts from which will therefore be found in this website’s main datasets (although where the Egerton book provides information on benefit night takings not found in the Aberystwyth book, we have included that Egerton information in our main datasets, too). The Egerton receipts and expenditure have been recorded as ancillary datasets. This is the receipts dataset; expenses are recorded separately.

Download Data

Charlotte Lane was one of Covent Garden manager John Rich’s daughters. She married a tailor, Robert Lane, who sometimes transacted with Rich’s theatre, Covent Garden; then, when he died, she appears to have taken over his business and continued transacting with Covent Garden. A document survives for the 1755-56 season, Folger, W.b.474, p. 397, itemising what she supplied to Rich personally and to the theatre, and what she was paid or owed for it. It provides a more detailed picture of clothing transactions than typically emerges from the theatres’ account books. No Covent Garden account book survives for the 1755-56 season, so the information here does not overlap or cut across any other information in this resource’s main datasets. However, Charlotte Lane’s transactions are too isolated and miscellaneous to include in the website’s main expenditure dataset, and, although Rich may well have funded the purchases attributed to his personal account from the theatre’s treasury, it is unclear whether he did on this occasion. The transactions have therefore been recorded as ancillary datasets instead: one for Rich’s transactions (‘Jno. Rich Esqr Dr. to Charlotte Lane’), here; one of the theatre’s (‘For the Theatre’).

Download Data

Charlotte Lane was one of Covent Garden manager John Rich’s daughters. She had married a tailor, Robert Lane, who sometimes transacted with Rich’s theatre, Covent Garden; then, when he died, she appears to have taken over his business and continued transacting with Covent Garden. A document survives for the 1755-56 season, Folger, W.b.474, p. 397, itemising what she supplied to Rich personally and to the theatre, and what she was paid or owed for it. It provides a more detailed picture of clothing transactions than typically emerges from the theatres’ account books. No Covent Garden account book survives for the 1755-56 season, so the information here does not overlap or cut across any other information in this website’s main datasets. However, Charlotte Lane’s transactions are too isolated and miscellaneous to include in the website’s main expenditure dataset, and, although Rich may well have funded the purchases attributed to his personal account from the theatre’s treasury, it is unclear whether he did on this occasion. The transactions have therefore been recorded as ancillary datasets instead: one for Rich’s transactions (‘Jno. Rich Esqr Dr. to Charlotte Lane’); one of the theatre’s (‘For the Theatre’), here.

Download Data

Receipts and expenses relating to James Brandon, a housekeeper and boxkeeper at Covent Garden. There are three, rather miscellaneous receipts, i.e. payments made by Brandon to the theatre’s treasury; and eleven expenses, one of which is a payment to Brandon for his salary, the rest of which are reimbursements to Brandon for payments he had made in his capacity as housekeeper. According to an entry on the receipts side, Mr Brandon was paid, or was at least due, the difference (£87 12s 10d) between his expenses total and his receipts total. Some, perhaps all, of the expenses were incurred during the summer between the 1792-93 and 1793-94 seasons. No dates are provided in this section of the account book.

Our rationale for separating this data from the main body of receipts and expenses is because the BL MS Egerton series of surviving Covent Garden account books does not cover the 1792-93 season, hence this season’s data is provided by BL Add MS 29948, which falls into an alternative series of account books spanning 1789-1809 (with gaps in coverage). The Egerton and alternative books are similar in many ways, and the latter may have been based on the former, but there are also some significant differences between them. Of most relevance here, comparison with seasons for which we have account books from both the Egerton and alternative series shows that the latter sometimes, at the end of the book, record data that, in the Egerton series, are instead recorded at the start of the following season’s book. This, or something similar, seems to have happened in the 1792-93 alternative book, where, at the end, there is a discrete section for ‘Mr Brandon’s Acct:’, followed by a discrete section for ‘Tradesmen’s Bills 1792 & 1793’. Comparing the ‘Tradesmen’s Bills’ section to the 1793-94 Egerton account book shows that there is indeed substantial, but not straightforward, overlap between the two. (See the introductory note to that dataset for more information.)

For Brandon’s account, the case is less clear. The entries are not evidently duplicated elsewhere. But the relevant pages do give a final balance, which they say is owed to Brandon; and one or more of the Brandons (i.e. him and/or his brother, John) are frequently paid in the 1792-93 and, especially, 1794-94 account books for unspecified reasons. Moreover, given that the ‘Mr Brandon’s Acct:’ section is treated on a par with the ‘Tradesmen’s Bills’ section, it seems fair to regard the former too as a set of data that overlaps with and itemises data found elsewhere. Hence it is recorded here as a discrete, ancillary dataset.

Download Data

A list of bills owed to tradespeople, presumably accrued but not paid by Covent Garden over the course of the 1792-93 season. Some of the records have the note, ‘Pd’ (i.e. paid), written at the end of them, but it is unclear when those notes were written; it seems unlikely that all or perhaps any of the records lacking that note were simply never paid. No dates are provided in this section of the account book.

Our rationale for separating this data from the main body of expenses is because the BL MS Egerton series of surviving Covent Garden account books does not cover the 1792-93 season, hence this season’s data is provided by BL Add MS 29948, which falls into an alternative series of account books spanning 1789-1809 (with gaps in coverage). The Egerton and alternative books are similar in many ways, and the latter may have been based on the former, but there are also some significant differences between them. Of most relevance here, comparison with seasons for which we have account books from both the Egerton and alternative series shows that the latter sometimes, at the end of the book, record data that, in the Egerton series, are instead recorded at the start of the following season’s book. This, or something similar, seems to have happened in the 1792-93 alternative book, where, at the end, there is a discrete section for ‘Mr Brandon’s Acct:’, followed by a discrete section for ‘Tradesmen’s Bills 1792 & 1793’. Comparing the ‘Tradesmen’s Bills’ section to the 1793-94 Egerton account book shows that there is indeed substantial overlap between the two – e.g. a £426 16s bill from the Enderbys is paid over several instalments in the 1793-94 Egerton book. But the overlap seems to be incomplete: some of the tradespeople mentioned in 1792-93’s ‘Tradesmen’s Bills’ are not mentioned anywhere else in our expenses. The payments to them may be disguised under differently-worded records, departmental expenses, etc., but that is impossible to trace. Given this substantial but not straightforward overlap, and the question around the ‘Pd’ notes, it seems reasonable to record the ‘Tradesmen’s Bills’, but separately from the rest of the expenses data, as has been done here.

Download Data

Drury Lane

The 1777-78 Drury Lane account book’s regular expenditure records includes payments into a Debt Fund, factored into the running total of expenditure. These have been recorded in this website’s main expenses dataset. However, the account book also includes memoranda – written in a different pen from the rest of the records and, crucially, not factored into the running total of expenditure – detailing what the money in the Debt Fund was used to pay (mostly tradespeople). There is no neat correspondence between the payments made into the Debt Fund and those made from it, meaning that the memoranda cannot simply be mapped onto the regular payment records. Thus the payments from the Debt Fund have been recorded as an ancillary dataset.

Download Data

At the end of Drury Lane’s 1786-87 account book is a ‘Payments of Old Debts’ section, with separate running totals of receipts and expenses from those of the rest of the book. The expenses enumerate the discharging of old debts, and total £1181 10s 10d. This money is covered by two receipts (or sums of money set aside for the purpose), one of which derives from the theatre’s main treasury as paid out in the 1786-87 season itself, the other of which from the theatre’s ‘Renters Interest & Balance’ account of the 1785-86 season (for which, see that account’s dedicated dataset).

Download Data

Drury Lane Renters

‘Renters’ were people who had bought a certain type of share of a theatre. They are sometimes compared to modern-day shareholders and/or bondholders, but the equivalence in either case is imperfect. Renters existed throughout the eighteenth century and although the exact nature of the arrangement varied over time and between the theatres, there were broadly consistent features throughout. Typically, a theatre would sell a batch of renters’ shares to fund building work, and each renter would then be allowed a free seat and a fixed payment (‘rent’) for each night’s performance. Shares could be bought and sold as the owner pleased, but tended to have a fixed expiry date, whereupon there was no redemption of the original capital, meaning that their value lessened over time.

An itemised list of the renters paid from the renters account (here cast as expenses) and of the money brought into that account to cover those payments (here cast as receipts). The theatre’s main treasury had paid £18 per acting day into a ‘Renters and Interest’ fund throughout the season (as recorded in the main expenses dataset), which money was intended to cover payments to renters and the interest due to David Garrick’s estate according to predesignated proportions. This was Drury Lane’s standard arrangement in the 1780s, but, in practice, the money did not always reach its earmarked recipients, and rarely did so in the predesignated proportions; and additional sources of money were sometimes drawn upon so as to cover the payments to renters and interest. In this case, the last two receipts clearly relate to such additional sources, but for most of them – those that mention ‘Bankers’ – it is unclear whether the money in question had come from the ‘Renters and Interest’ fund (i.e. the fund was maintained by the ‘Bankers’) or whether the ‘Bankers’ supplied money that had no connection to the ‘Renters and Interest’ fund.

Download Data

An itemised list of the renters paid from the renters account (here cast as expenses) and of the money brought into that account to cover those payments (here cast as receipts). The theatre’s main treasury had paid £15 per acting day into a ‘Renters and Interest’ fund throughout the season (as recorded in the main expenses dataset), which money was intended to cover payments to renters and the interest due to David Garrick’s estate according to predesignated proportions. This was Drury Lane’s standard arrangement in the 1780s, but, in practice, the money did not always reach its earmarked recipients and rarely did so in the predesignated proportions, and additional sources of money were sometimes drawn upon so as to cover the payments to renters and interest. In this case, it is unclear whether the receipts mentioning Martin & Co. concerned money that had come from the ‘Renters and Interest’ fund (i.e. the fund was maintained by Martin & Co.) or whether Martin & Co had no connection to the ‘Renters and Interest’ fund.

Download Data

An itemised list of the renters paid from the renters account (here cast as expenses) and of the money brought into that account to cover those payments (here cast as receipts). The theatre’s main treasury had paid £20, then £24 per acting day into a ‘Renters Interest & Balance’ fund throughout the season (as recorded in the main expenses dataset), which money was intended to cover payments to renters and the interest due to David Garrick’s estate according to predesignated proportions. (The term ‘Balance’ seems to have been used to denote the money paid by Linley and Ford, two of Drury Lane’s proprietors, to balance the money paid by the leading proprietor, Sheridan; that is to say, large payments were conceived as deriving from the proprietors’ shares of the theatre’s money, and, in some sense, first from Sheridan’s share.) This was Drury Lane’s standard arrangement in the 1780s, but, in practice, the money did not always reach its earmarked recipients, and rarely did so in the predesignated proportions; and additional sources of money were sometimes drawn upon so as to cover the payments to renters and interest. In this case, it is unclear whether the receipts mentioning Martin & Co. concerned money that had come from the ‘Renters Interest & Balance’ fund (i.e. the fund was maintained by Martin & Co.) or whether Martin & Co had no connection to the ‘Renters Interest & Balance’ fund. At any rate, the money found was not immediately enough; the money distributed to renters somewhat exceeded the money brought in for that purpose this season.

Download Data

This comprises a two-tier list. First comes an overview of the receipts into and expenses of the ‘Renters Interest & Balance’ fund. The theatre’s main treasury had paid £30 per acting day into that fund throughout the season (as recorded in the main expenses dataset), which money was intended to cover payments to renters and the interest due to David Garrick’s estate according to predesignated proportions. (The term ‘Balance’ seems to have been used to denote the money paid by Linley and Ford, two of Drury Lane’s proprietors, to balance the money paid by the leading proprietor, Sheridan; that is to say, large payments were conceived as deriving from the proprietors’ shares of the theatre’s money, and, in some sense, first from Sheridan’s share.) This was Drury Lane’s standard arrangement in the 1780s. In practice, though – as shown by the receipts and expenses recorded here – the money did not always reach its earmarked recipients, and rarely did so in the predesignated proportions; and additional sources of money were sometimes drawn upon so as to cover the payments to renters and interest. At this top tier of receipts and expenses, the money paid to renters is only given as two large sums, and the individual renters are not named.

The second tier then itemises the payments to individual renters. The total paid was £2956 4s, which is slightly less than the money set aside for the purpose according to the top tier (£370 12s plus £2605 16s, totalling £2976 8s). See also the ‘Drury Lane 1786-87. Old Debts account’ dataset, which was partially funded from a payment recorded in the top tier of this dataset.

Download Data

This comprises a two-tier list. First comes an overview of the payments made from the ‘Renters Interest & Balance’ fund. The theatre’s main treasury had paid £30 per acting day into that fund throughout the season (as recorded in the main expenses dataset), totalling £5490, which money was intended to cover payments to renters and the interest due to David Garrick’s estate according to predesignated proportions. (The term ‘Balance’ seems to have been used to denote the money paid by Linley and Ford, two of Drury Lane’s proprietors, to balance the money paid by the leading proprietor, Sheridan; that is to say, large payments were conceived as deriving from the proprietors’ shares of the theatre’s money, and, in some sense, first from Sheridan’s share.) This was Drury Lane’s standard arrangement in the 1780s. In practice, though – as shown by the expenses recorded here, and the receipts in the second tier – the money did not always reach its earmarked recipients, and rarely did so in the predesignated proportions; and additional sources of money were sometimes drawn upon so as to cover the payments to renters and interest. At this top tier, the money paid to renters is only given as a single large sum, and the individual renters are not named.

The second tier then itemises the payments to individual renters (here cast as expenses) and of the money brought into that account to cover those payments (here cast as receipts); most of the latter was the large sum paid out of the ‘Renters Interest & Balance’ fund, but three additional receipts were needed.

Download Data

An itemised list of the renters paid from the renters account (here cast as expenses) and of the money brought into that account to cover those payments (here cast as a receipt). The theatre’s main treasury had paid £30 per acting day into a ‘Renters Interest & Balance’ fund throughout the season (as recorded in the main expenses dataset), which money was intended to cover payments to renters and the interest due to David Garrick’s estate according to predesignated proportions. (The term ‘Balance’ seems to have been used to denote the money paid by Linley and Ford, two of Drury Lane’s proprietors, to balance the money paid by the leading proprietor, Sheridan; that is to say, large payments were conceived as deriving from the proprietors’ shares of the theatre’s money, and, in some sense, first from Sheridan’s share.) This was Drury Lane’s standard arrangement in the 1780s, but, in practice, the money did not always reach its earmarked recipients, and rarely did so in the predesignated proportions; and additional sources of money were sometimes drawn upon to cover the payments to renters and interest.

Download Data

An itemised list of the renters paid from the renters account (here cast as expenses) and of the money brought into that account to cover those payments (here cast as a receipt). The theatre’s main treasury had paid £30 per acting day into a ‘Renters Interest & Balance’ fund throughout the season (as recorded in the main expenses dataset), which money was intended to cover payments to renters and the interest due to David Garrick’s estate according to predesignated proportions. (The term ‘Balance’ seems to have been used to denote the money paid by Linley and Ford, two of Drury Lane’s proprietors, to balance the money paid by the leading proprietor, Sheridan; that is to say, large payments were conceived as deriving from the proprietors’ shares of the theatre’s money, and, in some sense, first from Sheridan’s share.) This was Drury Lane’s standard arrangement in the 1780s, but, in practice, the money did not always reach its earmarked recipients, and rarely did so in the predesignated proportions; and additional sources of money were sometimes drawn upon to cover the payments to renters and interest.

Download Data

A two-tier list. First comes an overview of the payments made from the ‘Renters and Interest’ fund. The theatre’s main treasury had paid £34 per acting day into that fund throughout the season (as recorded in the main expenses dataset) which money was intended to cover payments to renters and the interest due to David Garrick’s estate according to predesignated proportions. This was Drury Lane’s standard arrangement in the 1780s. In practice, though, the money did not always reach its earmarked recipients, and rarely did so in the predesignated proportions; and additional sources of money were sometimes drawn upon so as to cover the payments to renters and interest. At this top tier, the money paid to renters is only given as a single large sum, and the individual renters are not named.

The second tier then itemises the payments to individual renters (here cast as expenses) and of the money brought into that account to cover those payments (here cast as receipts); the latter came entirely from the ‘Renters and Interest’ fund, but was recorded in three separate components, corresponding to the status of and time at which the renters were paid from the money in question.

Download Data

An itemised list of the renters paid from the renters account (here cast as expenses) and of the money brought into that account to cover those payments (here cast as a receipt). The latter came from the theatre’s main treasury at the end of the season, recorded in the main body of expenses under 13 December 1791 as ‘By Cash carried to Renters Acct. Page 101’, £3914 16s. Essentially, then, the following list of expenses should be considered as a breakdown of that single expense record from the main dataset. However, note that the total amount paid to renters on this occasion falls short of the sum set aside for them.

Download Data

An itemised list of the renters paid from the renters account (here cast as expenses) and of the money brought into that account to cover those payments (here cast as a receipt). The latter came from the theatre’s main treasury at the end of the season, recorded in the main body of expenses account under 8 August 1792 as ‘By Cash Carried to Renters Account in this Journal Page 127’, £4065 10s. Essentially, then, the following list of expenses should be considered as a breakdown of that single expense record from the main dataset. Note that the total amount paid to renters marginally exceeds the money set aside for them, but only due to the three final payments, which seem to have been paid and recorded at a significantly later date than the rest, as they are not included in this section’s running total of expenses.

Download Data

An itemised list of the renters paid from the renters account (here cast as expenses) and of the money brought into that account to cover those payments (here cast as a receipt). The latter came from the theatre’s main treasury at the end of the season, recorded in the main body of expenses account under 9 August 1794 as ‘By Cash to pay 212 Renters 232 Nights for Performances under the Drury Lane Patent at Mr. Colemans & the New Theatre’, £4918 8s. Essentially, then, the following list of expenses should be considered as a breakdown of that single expense record from the main dataset. Note that the total amount paid to renters falls some way short of the money set aside for them.

Download Data

Drury Lane made four large payments into an Old Renters account in the early months of the 1799-1800 season (on 12 and 26 September 1799, 1 October 1799, and 10 December 1799), totalling £2372. They are recorded in the main body of expenses data. Following the record of the third payment – ‘3d. Paymt. to Old Renters making the Sum so paid in the whole £2,249. 16. 8 which was paid to the following Persons as pr. Banker’s Book’ – there is an itemised list of the old renters to whom that money was distributed, which is supplied here as an ancillary dataset. The total distributed does not quite reach the £2249 16s 8d initially specified, still less the £2372 subsequently reached; it is unclear what happened to the extra money or the Old Renters account thereafter.

Download Data

Drury Lane Certificates

Certificates are similar to modern certificates of deposit (CD). They were time deposits, meaning that they offered interest on the amount of money deposited according to a predetermined timespan; typically, the longer the term before maturity, the higher the interest rate. However, if the money was withdrawn early, it was usually the case that no interest would be paid. Certificates could also be used as collateral against further loans. At the start of the 1802-03 season, Drury Lane began recording certificates on the receipt pages of its account books, but with a separate running total from that of the other money received. These records continued with great regularity until Drury Lane’s conflagration in 1809, with new certificates being drawn on an almost invariable weekly basis. (They do not appear in DL’s second, post-fire account book for the 1808-09 season.)

The account books do not seem to record the purchase of, or investment in, any certificates, and it is therefore difficult to determine what was happening here. However, there are several clues. Most of the certificates recorded in the 1802-03 season provided round sums of money (e.g. £1200, no shillings, no pence). But from around 15 June 1803 onwards, the round sums disappeared; the values of all subsequent certificates were comparatively messy (e.g. £1916 3s 2d). This suggests that the theatre invested in certificates shortly before the 1802-03 season, and set their maturity dates at one-week intervals. However, due to the theatre’s cashflow problems, it began withdrawing the first set of deposits before they reached maturity, hence the lack of interest suggested by the round sums. Then, from around 15 June 1803 onwards, the certificates began to reach their dates of maturity, and the theatre was able to receive interest as well as the original deposits; hence the messier sums.

Another clue as to how the certificates functioned is provided in the 1804-05 season. On around 8 June 1805, there is a record for “Do. [Cash] in Certificate of 15th. June”, valued at £48 11s. Then on 15 June 1805, there is a record for a certificate valued at £1174 13s 8d, followed by a note: “NB This Certificate is 1,223: 4.”, minus “48: 11”, equalling “1174: 13: 8”. There follows in smaller, less tidy writing: “I have enter’d in the prior Week 48: 11: 0 which was omitted being the Constant Salary to Balance the Journal”. This refers to the certificate record entered on 8 June. The note suggests that certificates were indeed being mostly drawn on their correct dates, and it was an anomaly for any money to be drawn early. However, it is unclear whether there was any loss of interest for the premature partial withdrawal of the 15 June certificate: clearly £1223 4s was gained from the certificate in total, but it is unclear whether the sum would have been slightly higher if part of it had not been drawn early. It is also unclear whether the money was indeed drawn at two different times, in a smaller, then a larger portion; it may have been that the entire £1223 4s was drawn at one time – perhaps 8 June, but maybe even 15 June, if (as is possible, and sometimes seems to have occurred) receipts and expenses were not in fact received or expended on the dates to which they were assigned in the account books – and that the £48 11s was only assigned to 8 June because, as the scribe noted, that particular sum of money was needed to balance the books on that date (specifically, it seems, to pay the constant salaries).

There are several other things to note about certificates. First, on two occasions at the end of account books, money from benefit deficiencies was paid into the certificates’ running total. This may have been because the season’s main account had already closed for the season in question, whereas the certificate accounts remained, in some sense, open. These receipts have been recorded here. Second, the certificates’ records were not written in the most careful manner. Each new record was written under the running total for certificates, which was usually denoted by some such heading as “Cash by Certificates Brot. Forward”, with the individual new record mostly written by way of dittos, referring to the above heading. That means that most individual records include a ditto that refers to the word “Certificates”, despite the fact that the singular “Certificate” typically seems the more likely reading.

We would like to express our thanks to Charles Larkin for his detailed, considerate help in explaining how certificates worked, and in clarifying Drury Lane’s usage of them. Any errors of interpretation are of course our own.

Receipts & Expenses datasets

All Receipts

This is the consolidated Receipts dataset for both theatres. It consists of the ~27,600 Receipts that populate the relational database of this website, here rendered in spreadsheet form for user convenience. Each Receipt is drawn from the theatres’ manuscript account books and, in a few cases, from other sources. Almost all records of money received listed in the surviving account books for 1732-1809 are to be found here. Additional receipts data can be found in the other Ancillary Financials datasets on this page, with explanations as to why they are incompatible with our core dataset.

Each Receipt has fields for:

– A unique ID number. N.B.: this does not fulfil the function of the Expense sequence number (#) field, for which the Receipts have no equivalent.

– The Theatre that received the money.

– The Payment Date in the YYYY-MM-DD format, for ease of sorting.

– The Calendar Season, referring to which season it fell in chronologically, rather tha which season’s account book it was recorded in. Our season runs from 1 September and to 31 August. N.B. Receipts do not have the Account-Book Season information given for expenses.

– The Event ID, referring to the Event (i.e. a particular performance night at a particular theatre) that generated the Receipt in question. The number refers to the unique ID assigned to each Event in the database. Only door receipts are linked to an Event ID; for other receipts, the field is blank. Most Events only have a single item of door receipts attached to them (if they have any at all), but in a few cases the account books recorded more supplementary door receipts information than could be fit into our data fields (see below), so the additional supplementary receipts have been recorded as an additional Receipt, linked to the same Event.

– A Notes field, for the narrative entry written in the account book. Most Receipts are straightforward door receipts, and therefore have no need for Notes. Where an item of door receipts includes supplementary income (i.e. not one of the standard types of – first price, half-price, or aftermoney – but some such unusual type as ‘Odd Money’), the description thereof is transcribed into this field from the account book. For non-performance receipts, the Notes field is used for the transcription of the entry from the account book, e.g. ‘Mr. Condell’s 3d. Payment in full for Fruit Office’, occasionally with our own annotations added in square brackets in a practice that differs with how we have treated Expenses.

– A Category field, and an Umbrella Category field. Receipts are fewer and simpler than expenses: there are ~27,600 Receipts against ~158,000 Expenses, and ~70% of Receipts are door receipts. Therefore, there are far fewer Receipt than Expense Umbrella categories and categories: 6/24 as against 12/147. In addition, resources did not allow for dedicated categorisation work on the non-performance Receipts, some therefore are marked ‘Uncategorised’ (~1200). In practice, ‘Uncategorised’ therefore collects the sorts of transactions that, if Expenses, would have been categorised ‘Miscellaneous’ or ‘Unknown’.

– A Person ID field, giving the unique ID numbers for the Person(s) attached to the Receipt (if any), and a Person Name field, giving their display names. The Person(s) attached were not necessarily those who paid the money into the theatre; they may simply be named in the Notes. Due to time constraints, Persons have been attached to Receipts illustratively, rather than comprehensively.

– A series of monetary fields. These are very numerous, and many of them are unpopulated for most Receipts, because they convey different levels of detail, and our financial sources are wildly inconsistent as to which level of detail they record. For example, one account book might give such information as the half-price pit receipts, whereas another book might only give the total door receipts. The most important fields, and those which are populated for every Receipt, are ‘Total Pounds’, ‘Total Shillings’, and ‘Total Pence’: all monetary figures recorded in any of the other fields will be factored into these ‘Total’ fields.

There is also a second tab, laying out the receipt Categories (including Umbrella Categories) and their definitions.

This is the Receipts dataset for Covent Garden only, a matching subset of the ‘All Receipts’ spreadsheet.

Download Data

This is the Receipts dataset for Drury Lane only, a matching subset of the ‘All Receipts’ spreadsheet.

Download Data

All Expenses

This is the consolidated Expenses dataset for both theatres. It consists of the ~158,000 Expenses that populate the relational database elsewhere on this website, here rendered in spreadsheet form for user convenience. Each Expense is drawn from the theatres’ manuscript account books, and almost all expenditure records listed in the surviving account books for 1732-1809 are to be found here. Additional expense data can be found in the other Ancillary Financials datasets on this page, with explanations as to why they are incompatible with our core dataset.

Each Expense has fields for:

– A sequence number (#). This orders the entries by theatre, then account book, then by the order in which the Expenses are recorded within each book. All Covent Garden books are sequenced first, followed by all Drury Lane books. Thus #1 is the first item in the earliest surviving Covent Garden book, for the 1735-36 season. The sequence numbers mostly, but not entirely, follow chronological order within each theatre. Exceptions occur because, in a few cases, the books list items out of chronological order; and, more often the case, the books list items under dates that fall outside of the season in question (chronologically speaking). For example, the 1767-68 Covent Garden book records payments all the way to 6 June 1769, overlapping considerably with the dates of the payments recorded in the 1768-69 book, meaning that many of the items from the 1767-68 book have an earlier sequence number than items recorded on earlier dates in the 1768-69 book. Users interested in the chronological order can refer to the Payment Date field instead (see below).

– A unique ID number.

– The Theatre that made the payment.

– The Payment Date in the YYYY-MM-DD format, for ease of sorting.

– The Account-Book Season, meaning the account book from which the data comes. Thus, all Expenses recorded within the Covent Garden 1767-68 book are assigned ‘1768-1769’ in this field, even when they fall into the date range of the 1767-68 season. This field contrasts to the following field, providing users with different ways of exploring the data. N.B. ‘Account-Book Season’ is not used in the database, where Calendar Season is used throughout.

– The Calendar Season, referring to the season in which the expense falls according to our fixed date rubric where a database season runs from 1 September to 31 August (see Introduction for our rationale), rather than the season’s account book in which it was recorded. Thus, the payments recorded in the Covent Garden 1767-68 book that fall in the 1768-69 season (as defined 1 September 1768 to 31 August 1769) are assigned ‘1768-69’ in this field. This field contrasts to the preceding field, providing users with different ways of exploring the data. N.B. When using the spreadsheet, users may wish to hide either the ‘Account-Book Season’ or ‘Calendar Season’ column, to avoid confusing the two.

– The prose Entry. This is a verbatim transcription of the prose narrative written in the account book to describe each payment.

– A Category field, an Umbrella Category field, and a Payment Type field. Together these fields comprise the categorisation system implemented on the Expenses. There are 12 Umbrella Categories, each identifying a major area of theatrical expenditure, collectively dealing with 141 individual Categories. The relationship between each Category and its Umbrella Category is fixed: all payments classified ‘Housekeeping’ in Category fall under ‘Upkeep and Refurbishments’ in Umbrella Category. However, Payment Type operates independently of the other two fields, merely conveying whether the payment in question was ‘Departmental’, ‘Internal’, ‘External’, or ‘Unknown’.

N.B. because of the inconsistencies and opaqueness of the account books’ records, it should not be assumed that any Category comprehensively captures all Expenses that might potentially have fallen within its remit. For example, a payment to a specific actor will be categorised ‘Actors’, but a single payment to an actor and a singer conjointly will be categorised ‘Performers (Other)’, and a single payment to the theatres’ actors alongside its singers, dancers, and backstage staff will be ‘Employees (Other)’. The Umbrella Categories have somewhat stabler boundaries, but even they suffer porousness; most notably, because Drury Lane’s account books between 1749 and 1799 recorded single weekly payments to all its employees on per-diem salaries, including musicians in the house band, its expenditure on the house band for that period is lost in the ‘Personnel’ Umbrella Category, rather than being included in the ‘Music’ Umbrella Category to which it theoretically belongs as we cannot distinguish between actors and musicians, or indeed any other employee categories.

– A Person ID field, giving the unique ID numbers for the Person(s) attached to the Expense (if any), and a Person Name field, giving their display names. The Person(s) attached were not necessarily those whom the theatre paid; they may simply have been mentioned in the Entry in association with the payment. Due to time constraints, Persons have been attached to Expenses illustratively, rather than comprehensively. Most Expenses have no Person attached, and, in most cases, the reason was rather lack of time than the obscurity of the transaction in question.

– Monetary fields for the pounds (£), shillings (s), and pence (d) paid.

– A Notes field for our own interpretative/explanatory comments, where necessary. Most Expenses do not have

Notes.

There is also a second tab, laying out the expense Categories (including Umbrella Categories) and payment types, and their definitions.

This is the Expenses dataset for Covent Garden only, a matching subset of the ‘All Expenses’ spreadsheet.

Download Data

This is the Expenses dataset for Drury Lane only, a matching subset of the ‘All Expenses’ spreadsheet.

Download Data